Maureen Duffy at 80: In Times Like These

FIGHTING AND WRITING

Header image: Maureen Duffy with Massimiliano Di Carlo and Anna Maria Robustelli, copyright Cinzia D'Ambrosi, 2019.

Recognising writers: responses, records, royalties

by Katie Webb

I want to reflect on some of the work I’ve been doing with Maureen, namely as part of the International Authors Forum. The International Authors Forum and I are only very recent additions to a long history of work for authors’ rights, in which Maureen has had and continues to have a much bigger part. So this paper is very much a story so far, as much as a very recent history. It is also about today as the beginning of the Strandlines project, which has been mentioned a few times already. And as this paper is a reflection on beginnings, fittingly, I thought I’d begin with an end.

In Nadine Gordimer’s obituary of Chinua Achebe earlier this year, she described Achebe by quoting Albert Camus who said, “The day when I am no more than a writer I shall cease to be a writer.” Maureen referred me to Gordimer’s article, as part of my work with her, forging an initiative called the International Authors Forum – or IAF for short. The IAF is the latest in a long line of organisations to which Maureen is devoting her energy, when she is not writing – it is part of the fighting this panel connotes. And it takes place so that she, and her fellow writers, can get by as writers, whose names – unlike these eminent forbears - we may never know, but whose work is of value in their locality, field of interest or community as writers, the meaning of which Camus’ quote might prompt us to question.

Whatever technological guise writing takes by the time we read it, from runes inscribed on a monument, to words converted to computer data and displayed as words again on a device that can be accessed anywhere, it starts with the human individual putting their ideas into material form and sending them out into the world. Receiving a letter from Nadine Gordimer herself affirmed this for me. After reading Gordimer’s obituary of Achebe in which she talked about his activism for authors in Africa, Maureen suggested I write to Gordimer, in South Africa, to tell her about the International Authors Forum. In an unexpected response, I received a handwritten letter from Gordimer, voicing her support for this new initiative. To hold a piece of paper containing words that have been written on another continent by the same hand that has written Nobel-winning literature is a strong reminder of how indispensable the human being is to creative endeavour, and its continuity. Receiving Gordimer’s letter was a symbolic moment – perhaps more so than the words on the page. That Gordimer had taken the time and effort to write back, in fact to copy her letter and send it again, for I received it twice, made the individual behind the writing visible again. Being active between communities of authors – writers and visual artists – in different parts of the world, and between the organisations that support them as individuals – providing them with a forum: this is what the IAF seeks to do – to remind the world, which still gets by and is made richer using authors’ work, that authors are still here and they must get by too.

When I came to work for the International Authors Forum as its administrator, it was with the idea of helping to make it into an active, independent entity, at Maureen’s behest. The IAF had been in conception for quite some time: discussed between international representatives of authors, who had met collectively as the International Authors Forum. Maureen has always worked to preserve this value for all authors, no matter where they are, and no less today – not just to talk about it. The IAF is a squaring up to, in particular, the threats that digitisation and globalisation pose to copyright: the ease of making a copy, at the touch of a button, which makes it easy to forget the value of the original, and its human origin. Indeed where better to remind us of this than in the European Declaration of Human Rights, also found on the front page of the IAF’s website. Article 27 (2) says that “everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.” The moral and material interests of authors are catered for to varying degrees in different parts of the world, but they are also considered globally. This is the work of the World Intellectual Property Organisation, or WIPO, which is the branch of the United Nations that forms international policies on intellectual property, including copyright, which most concerns authors. Lately, authors have been in danger of being left out of WIPO’s concerns amidst the cacophony of other voices that have interests in their rights and are also at risk of infringing them: publishers, libraries, cultural and educational institutions, customers, consumers, users and readers, among others. Maureen has been representing an author’s voice internationally at WIPO to redress that balance, to reiterate the author’s existence in the world, the importance of the space they occupy – to say very clearly “we are still here”, no matter how much happens between something being written and being read.

This specific International Authors Forum is at a rudimentary stage, although it is part of a long history of authors uniting internationally to respond to particular needs at particular times. In these times, technology is allowing access to more people, and more places, literally and virtually. This means more people to meet, more stories to exchange, more ways to listen and fewer reasons not to. The job of the IAF is not just to speak on behalf of authors but, importantly, to listen to them too, to understand and try to balance differing needs and help preserve the viability of being an author, anywhere. I want to draw on the perspective I gained from the story of one particular author whom I was fortunate to listen to recently.

Often, the value of something is not noticeable until it stops working; running water; running trains, on time... The Turkish writer Kaya Genc, addressing the International Authors Forum in Istanbul last month, told us his story of the choice that had been effectively taken away from him in 2008, forcing him to give up what he termed his “authorial freedom” by signing an employment contract to write for Newsweek magazine, to which he would have preferred to make contributions as a freelance writer. “The editor reminded me,” he told us, “that the category of freelance writers simply didn’t exist in Turkey…if you wanted respect, you needed to become part of your publication’s institutional structure.” Of course, the writer was to be paid; but the value of his work was not considered in terms of its owners’ copyright – his right to choose what happens to it - on the contrary, he was told that his ambition to make a living saying what he wanted to say in his own words, rather than as the mouthpiece of Newsweek, no more than a writer, or a writer of copy, was futile.

Of course, all authors negotiate, like the rest of us, between what they want to do and how they can sustain themselves doing it. To constitute proper payment, enough money is critical, but if there is no market in which to negotiate, the value of the author as an individual voice will become void, whether that is consequentially, because the human individual is forgotten amidst the brands that trade on her words, which are ever more easily replicated mechanically, or because of a repressive regime, where individual rights don’t count.

The possibility of having literary space for lots of writers’ imaginations was, at the time and in the place Kaya described, unwanted and made unimaginable. More than that, it was positively persecuted. In Turkey, trying to create that space by writing it, under your own name, meant you could be killed. Kaya, in London a respected writer with freelance contributions to a plethora of respected publications, had, in his home country, been subjected to a police investigation about a fiction he had written in his own name. His case was only dropped, ironically, because of the protection his identity as an employee afforded him. Kaya, whose freedom of expression was denied him, told us “There is no better way of showing your gratitude and appreciation for a writer’s work than paying them properly for their labours.”

The eternal challenge for writers, of getting their work into the spaces where it can and will be read, and vitally, recognised as theirs, is calling for more and more writers to become their own agent, negotiator, publisher, publicist and more. Copyright seeks to strike a balance, recognising the interdependence between writer and reader to sustain value in creativity – which means proper payment. Readers have a responsibility to respect the provenance of the writer and the choices she makes about the terms on which she is recognised. Writers have a responsibility to think about the consequences of their words upon their fellow human beings, when they set those terms.

This fighting for writing, which is also writing as fighting, takes place to ward off the day when a writer might become, as Camus puts it, “no more than a writer”, when writing serves as a no more than a description of a mechanical, physical, perhaps even an historic process, putting pen to paper absent the imagination of a person. If we stop listening to individuals and recognising them as individuals, we might not notice they are missing from the page, until they are gone.

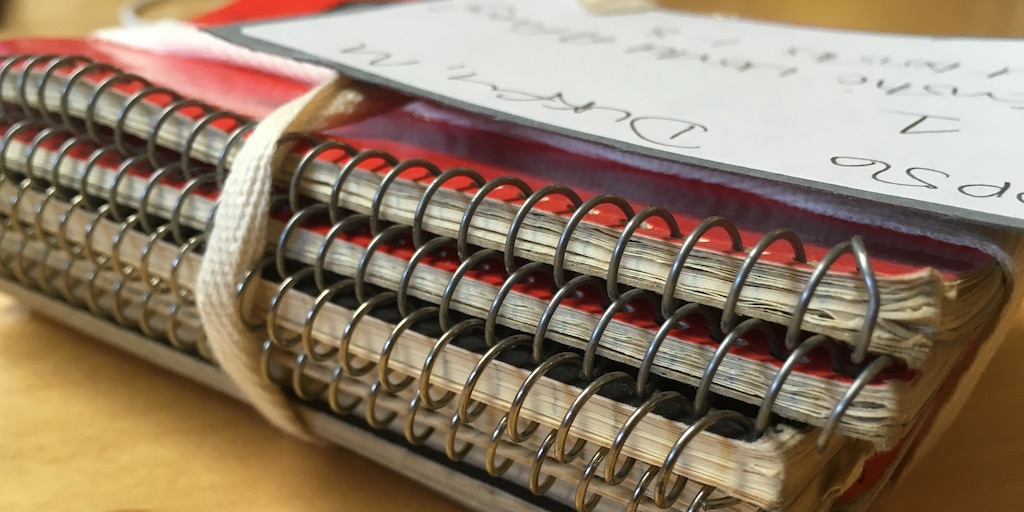

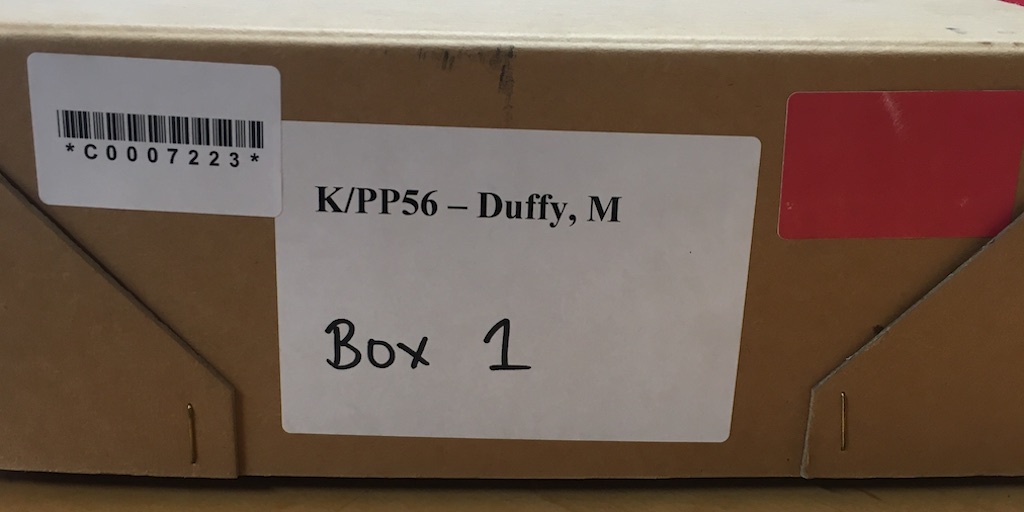

It was as a student of English Literature here at King’s that I first met Maureen, working for her with her archive, which she is donating to King’s and about which we’ll hear more in the next discussion. I learned during my degree that literature is important for its own sake, and as a component of the world it’s situated in, because of the ideas we can trace and explore through it, in responsive and receptive ways. My more recent education has involved the moral and material significance with which copyright imbues authors’ works here and now. I have been preoccupied with reconciling these two value systems in terms of each other. This process has mutually enriched the personal value I ascribe to each and allowed me to situate myself within them, as a constituent part of world I live in, with the hope of beginning to be able to give back, in thinking about rights to consider my responsibility as a constituent part.

An archive is a physical place where we can go to trace, through material records, how the subject of that archive, or the version of it that we know, came to acquire that meaning – a record of its situation in the world. The records stored might be anonymous or attributed to individuals. From an archive we can uncover voices from the past that perhaps went unrecognised, gain perspectives from other times and places. It also invites new responses, continuation, exploration of memories stored.

It is rare that Maureen’s many contributions, the many worlds she inhabits, people to whom she speaks and speaks up for, are considered in one place. Those strands are drawn together, here on the Strand, today, in order to recognise and celebrate the value of an individual. I hope you will by now have learned of Strandlines, the online digital community run through The Centre for Life-Writing Research, which is also hosting this day. Strandlines is a live archive, a store for information and an interactive forum in the form of a website, that traces lines and lives from and to the Strand. Today’s event will be documented on Strandlines to enable those who couldn’t be here today, of which there are many, to make their own contribution, and to allow those who are here to revisit it and contribute more. Your programmes have details, and I invite you to visit the Strandlines website and leave your contribution there, be it a reaction to today, to another aspect of Maureen’s work, or a personal or birthday message you wouldn’t mind making public. It will, we hope, both contribute to and strike a balance with her own archive, one a record of what is behind her value, and the other of how that value is augmented by the responses it continues to elicit and inspire, but which we can still firmly trace to Maureen, and some of that can be traced here at King’s.

Continuing to iterate the importance of the individual in the cultures and communities we value, be that by proper payment, contributing to academic or social conversations, or by advocating their rights, is important. Through exchanging words and experiences we become educated in how to achieve this. Maureen’s mother, who’s birthday it is today, and who clearly knew Maureen was in for a fight, treasured education as “the one thing they can’t take away from you”, to use Maureen’s words. Maureen thanks her mother for her achievement, as well as many writers from all ages, as we see evidenced in her writing. She uses that education in novel and startlingly imaginative ways, as a writer, to make things happen, to connect people and places in word and in deed. And we should make something of that, as, I hope we are beginning today. As a writer she is also a fighter, and her unceasing energy to do both shows us that however solid the foundations laid in the past, of which we should definitely take note, we must always be ready to carry on, and begin that fight again.

Sections and Chapters

Duffy and King's introduction

Katie Webb

Finding Maureen Duffy in the Archives

Patricia Methven

King's in Maureen Duffy's time

Christine Kenyon Jones

Kings, and Queens, Histories in Fact and Fiction

Clare A. Lees

Panel Summary: the city as a space for new possibilities

Phoebe Blatton

Writing, Rites, and Rights

John Stokes

A Window for Maureen Duffy

Clare Brant

Fighting and Writing introduction

Katie Webb

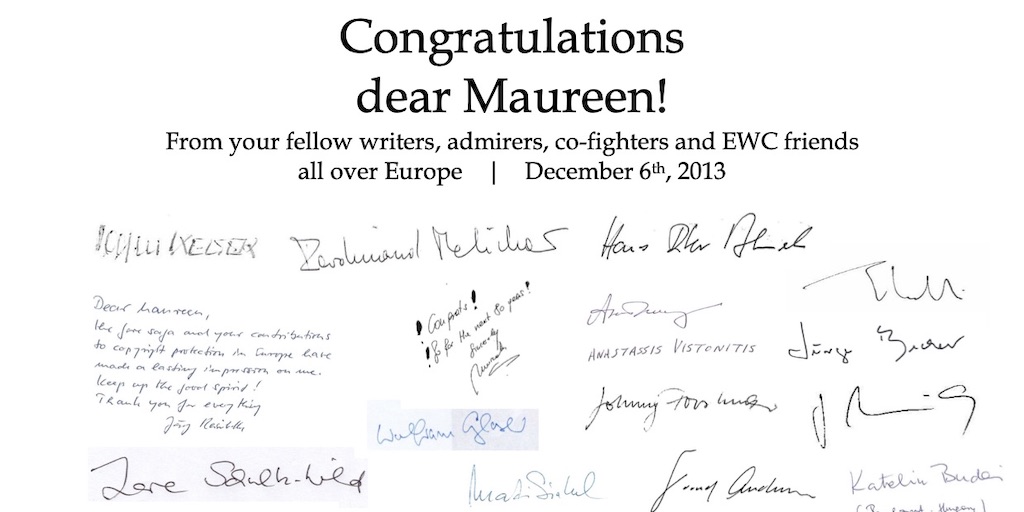

Duffy and the European Writers' Congress

Lore Schultz-Wild

An 80th Birthday Honorific Speech

Ingrid Protze

Memories of the German Writers' Union

Sabine Herholz

On Maureen

Katalin Budai

A copyright warrior and a true defender of rights

Olav Stokkmo

Recognising writers: responses, records, royalties

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy's contribution to gay rights and lesbian visibility

Jill Gardiner

For Maureen Duffy, Poiêtes

Karen Gevirtz

Editor's introduction

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy: Scrivener and Prophet

Charles Lock

Words that count: Maureen Duffy

Marina Warner

Copyright Cinzia D'Ambrosi 2019. Maureen Duffy reads her poetry at an event hosted by the Writers' Union of Italy (FUIS) in association with Alberi Di Maggio, at Rossodisera restaurant, Covent Garden, London, 26th March 2020. Maureen appears in the photo with musician and researcher Massimiliano Di Carlo and translator Anna Maria Robustelli.

Browse articles on Fighting and Writing