Maureen Duffy at 80: In Times Like These

DUFFY AND KING'S

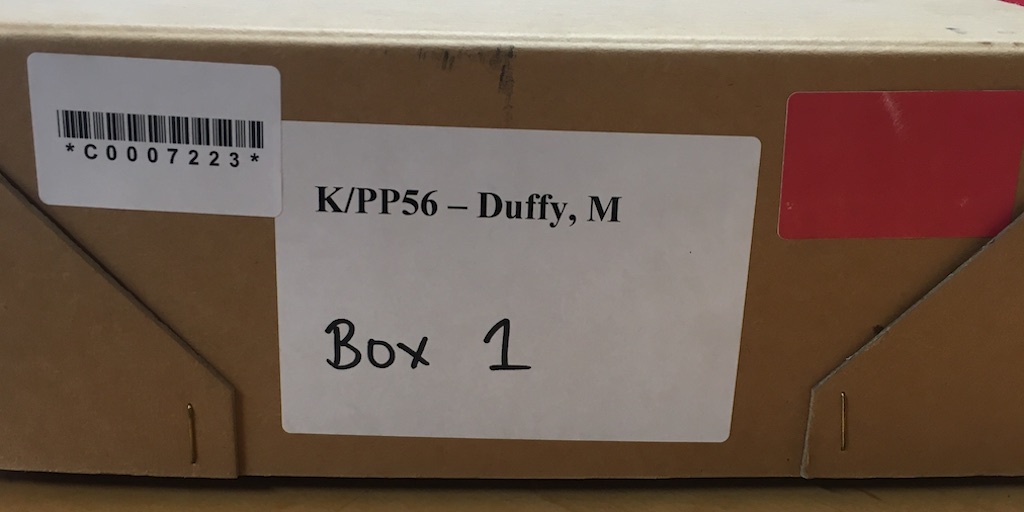

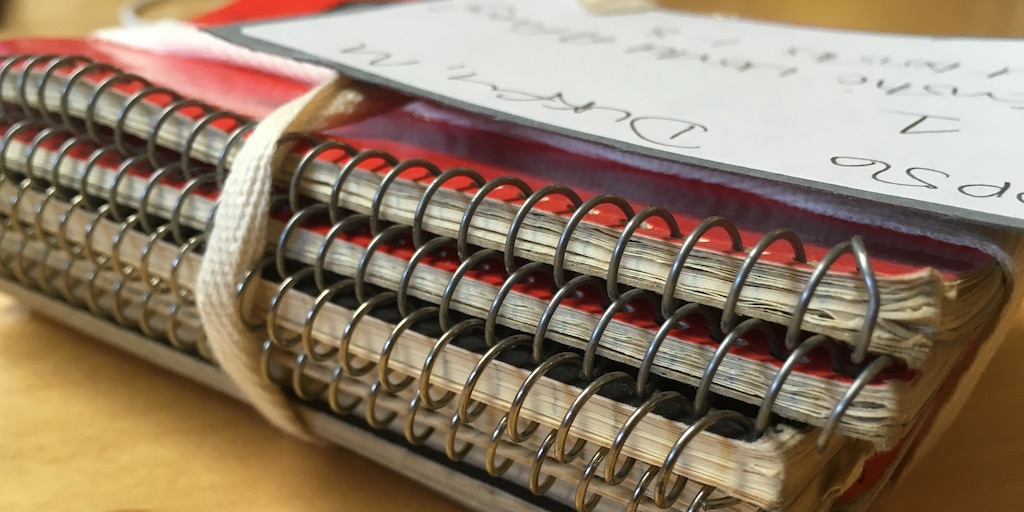

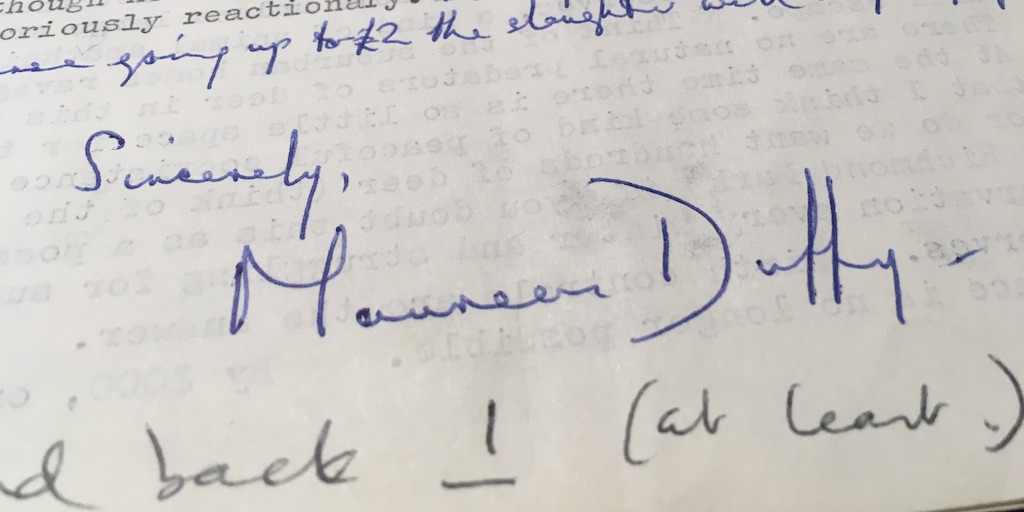

Header: detail from a letter sent by Maureen Duffy to Mr Harris, 10 August 1970. Held at K/PP56, Box 11, King's College London Archives.

Writing, Rites, and Rights

by John Stokes

Maureen cares about writers and writing as well as rights - writers and writing of every possible kind. I may be the first but I won’t be the last today to make that point. And it’s worth making at a time when we are all, academics in particular, forever being told to specialize – asked to declare what our ‘special interests’ might be. Where we fit into the frame.

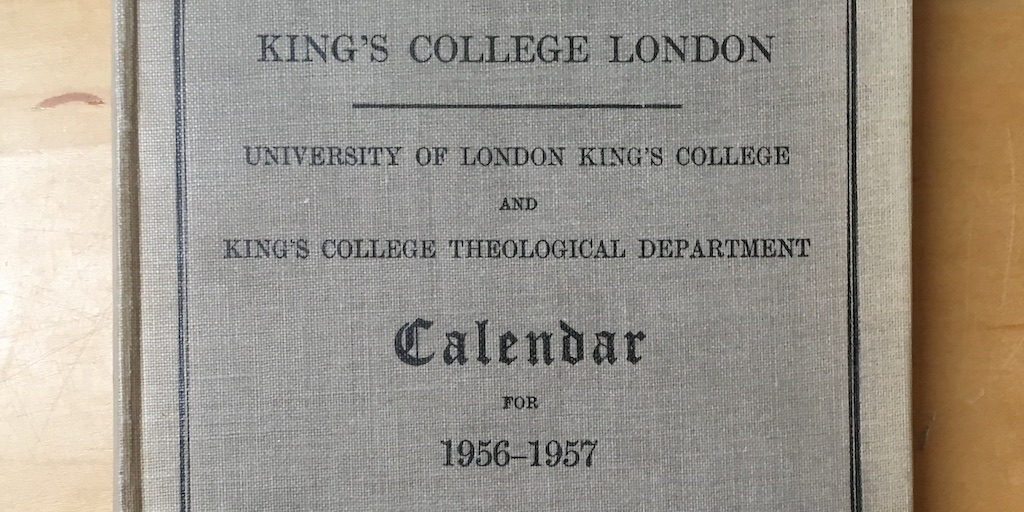

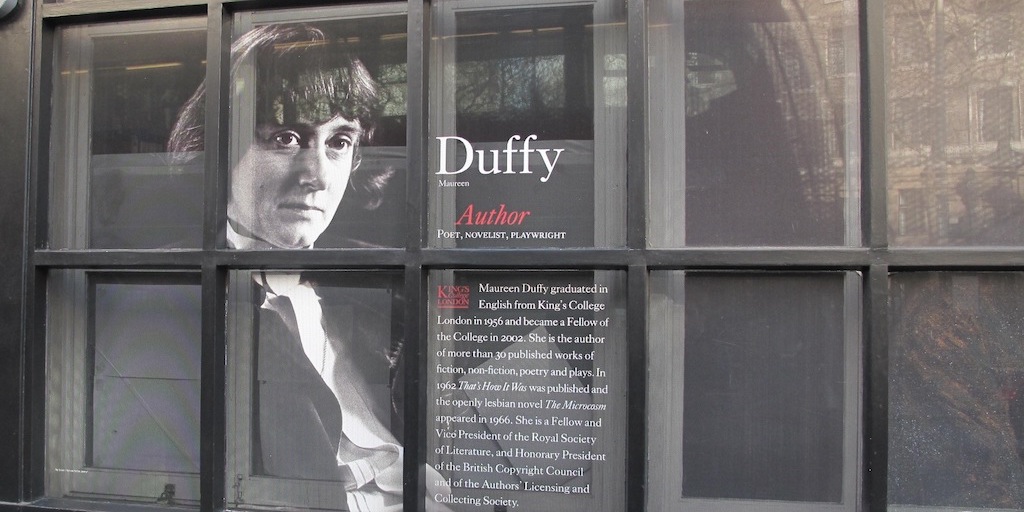

Sometimes those frames – frameworks, REFs – can feel like prisons. Maureen Duffy knows no frames; she isn’t a specialist; she’s an enthusiast and an expert. And I’d like to think that her enthusiasm and her expertise – extraordinary both - stem, at least in part, from King’s where she studied as an undergraduate and an inclusive, ever-expanding sense of what literature is and what it can do.

Look back over the syllabus at King’s as it has evolved over the years and you do get a real sense of that. Medieval studies, always, uniquely strong here, Shakespeare and the seventeenth century, work on the tradition of the novel, on drama, on poetry of all periods, the pioneering introduction of American literature through to today with post-colonial studies, life-writing, and work on gender and sexuality.

It’s in the context of ‘gender and sexuality’ that we might think most obviously of Maureen’s pioneering, but never less than provocative, example. Those extraordinary books, ‘queer’ before their time, in which Maureen took the idea of gender and like Oscar Wilde describing Lord Henry Wotton in The Picture of Dorian Gray, ‘tossed it into the air and transformed it; let it escape and recaptured it; made it iridescent with fancy, and winged it with paradox’.

Today King’s English also offers courses on urbanism (and we won’t be allowed to forget that Maureen is a quintessentially London novelist) together with something that Maureen and her generation might not have foreseen: ‘Creative Writing’ at King’s – though Maureen taught the subject herself up the road at the City Lit. (‘Hard work and badly paid’ as a character remarks in In Times Like These, the very latest novel.) Of course, all writing is creative in one sense or another – another lesson to be learned from Maureen’s career.

And sometimes it’s ‘collaborative’ as well as ‘creative’, most of all in the theatre. The punning title of what was for a while Maureen’s most notorious play, Rites, takes us straight to the heart of her concerns, which she shared at the time with some distinguished others. Rites was first presented by the National Theatre Company on 8 February 1969 and Maureen herself has told us how that production came about:

'One late afternoon in summer 1968 a group of people were gathered in the Oliviers’ flat in Victoria. They were Joan Plowright and Lawrence Olivier, Margaret Drabble, Gillian Freeman, Sheena Mackay, Penelope Mortimer and me, and it should be clear at once from this cast list what the meeting was about. Joan Plowright, intensely aware from her position within the National Theatre company of the shortage of good contemporary roles for actresses, and of women writers and directors in the theatre, had decided to exercise some positive discrimination. The assembled writers, known chiefly for their work as novelists were all to try their hands at writing a one act play and the National would stage such of the results as were stageable in an evening that came to be known as Ladies’ Night.'

Where, I wonder, was that piece of history in all the recent ho-ha celebrating 50 years of the National?

No sooner do you think that you’ve listed all Maureen’s enthusiasms - medieval, classical, seventeenth century – poetry, novel, drama - than you stumble on yet more. I’ve just been re-reading her 1973 novel I Want To Go To Moscow. Hard to describe, it’s a kind of comedy thriller with a serious theme which takes its title from Chekhov, it’s epitaph from Dante and in the first twenty or so pages ‘references’ (as people say these days) Dickens, children’s rhymes, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, Karl Marx, Franz Kafka, Alexandre Dumas, Marlene Dietrich… and then towards the end less surprisingly Dido’s great lament from Purcell’s opera. For Maureen something of a sacred text – or score.

As for London: again, wide-ranging, but not just historically, topographically. Reading Maureen’s work you keep on encountering places you know or once knew. The other day I was re-reading her novel Capital published in 1975 when I came across this passage about stepping off the Central Line at Stratford East – which is near where Maureen spent some of her girlhood.

'Now the line ran alongside Roman Road and under the river Lea to swing Northeast into Stratford Marsh. If he could have jumped off here, Meepers thought, as they clattered up into the night, it might have saved him a lot of walking. As it was he got meekly out at the station leaving the train to scurry off towards Epping Forest, its deer and sleeping cattle.

Outwards he was horrified at how much had been done since he was here last. Would he be able to find his way in? A giant had laid about him laughing, with his sledge-hammer. Then he had come back with Herculean bucket and spade and built great sandworks, bastions and ramps which had set fast baked by the summer sun and mixed with his own piss and spit. Where there had been cottages and barrows in little well proportioned streets there were ziggurat car park and supermarket, launching pad flyovers and moonrocket tower blocks among which clung the old Royal Theatre, a shrunken decayed shabby gentlewoman dwarfed and pitiful. The foundations to all this must reach the earth’s core. Nothing could be left.'

That happens to be my own experience exactly because it’s a cityscape I knew quite well when young in the 1950s and then revisited by chance after some 20 years absence.

Since the writing of Capital the Theatre Royal, workshop of the great Joan Littlewood (shabby perhaps but no gentlewoman she) has been preserved and re-born – not that the one always leads to the other - and we’ve had the Olympics, of course. To step off the Central Line at Stratford now is to be doubly, trebly shocked. I wish Maureen would write about it, but perhaps she has since the up-to-date production of Purcell’s King Arthur that takes place in the unspecified future of In Times Like These is compared there to the London Olympics of 2012 – ‘everything’s constantly shifting. If you look away you miss something.’ Maureen’s vision exactly. City and nation – always shifting, always connected.

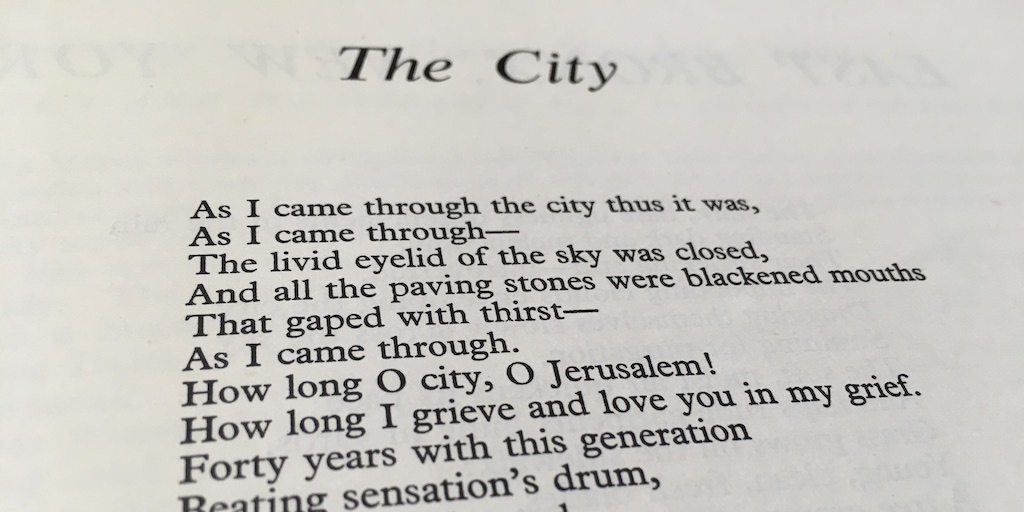

And as I’m getting personal I want to mention another kind of connectedness. I want to quote from her latest book of poems and a passage about Saint Cuthbert, the 7th century saint who lived on Lindisfarne with the animals:

And the sleek otters who came ashore

to dry him with their fur, rubbing against

chilled legs and belly so he could join

the others at service while they slipped

away back into their watery zones

do they suggest Cuthbert knew even then

our world was one, living and breathing

he whose hunger was slaked by the sea eagle’s

catch, the mighty fish he ordered to be cut in two

and the great bird given back its half share.

As always with Maureen this is an appropriation of myth that’s also an activation. Ancient Ecology, Holistic History. Connectedness.

There’s food again in her latest novel, In Times Like These – though no ‘mighty fish’. At the end its two heroines, a partnership in every sense, go off to celebrate in a restaurant actually on the Strand. In Times Like These has, typically, two interwoven narratives – one set in AD 600, one in the future post Scottish independence – both about separation except that separation only leads to more complex forms of interdependence and new beginnings.

‘Where shall we go now?’

‘The world was all before them where to go

And providence their guide…’

‘What’s that?’

‘The end of Paradise Lost. The English version of the Sistine chapel.

‘I don’t want paradise lost. I want us to keep it.’

‘well Milton didn’t really think they’d lost it.’

‘It just makes me remember a terrible painting by Masaccio where Adam and Eve are being expelled from the garden, and their howling with pain and grief.’

‘Milton doesn’t send them off like that at all. He has them hand-in-hand wandering slowly through Eden.’

‘That’s more like it. Come on then. Let’s find somewhere to eat. I don’t think Providence is going to provide.’

‘There’s the Inferno and Paradiso in the Strand.’

‘Sounds perfect.’

Sadly, walking down the Strand the other day I noticed that the old familiar Italian restaurant the Paradiso e Inferno seems to have gone. A fact that demands Maureen immediately write a sequel to In Times Like These, brings it up-to-date in her unique way.

We can always be certain when we start reading something by Maureen that it will be about a past, ‘then’, and it will somehow be about ‘now’, and about a future ‘then’ – past, present and future connected within the covers of a book that is about how people have lived, how they live and how they might live. And about where they live. And it will be infused with a sense of literary inheritance.

I can only think of one genre of which this might not inevitably be true and, as it may not otherwise get a mention today, I’ll mention it now. The Celebrity Vegetarian Cookbook published in 1988 had some impressive contributors: Paul McCartney, Joanna Lumley, John Peel, Spike Milligan, Glenda Jackson, Twiggy, Yehudi Menuhin – and, of course, Maureen Duffy with ‘Spaghetti Napoli’. Which is sure to be a delight. Like everything else Maureen has cooked up for us over the years.

Sections and Chapters

Duffy and King's introduction

Katie Webb

Finding Maureen Duffy in the Archives

Patricia Methven

King's in Maureen Duffy's time

Christine Kenyon Jones

Kings, and Queens, Histories in Fact and Fiction

Clare A. Lees

Panel Summary: the city as a space for new possibilities

Phoebe Blatton

Writing, Rites, and Rights

John Stokes

A Window for Maureen Duffy

Clare Brant

Fighting and Writing introduction

Katie Webb

Duffy and the European Writers' Congress

Lore Schultz-Wild

An 80th Birthday Honorific Speech

Ingrid Protze

Memories of the German Writers' Union

Sabine Herholz

On Maureen

Katalin Budai

A copyright warrior and a true defender of rights

Olav Stokkmo

Recognising writers: responses, records, royalties

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy's contribution to gay rights and lesbian visibility

Jill Gardiner

For Maureen Duffy, Poiêtes

Karen Gevirtz

Editor's introduction

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy: Scrivener and Prophet

Charles Lock

Words that count: Maureen Duffy

Marina Warner

Browse articles on Duffy and King's