Maureen Duffy at 80: In Times Like These

DUFFY AND KING'S

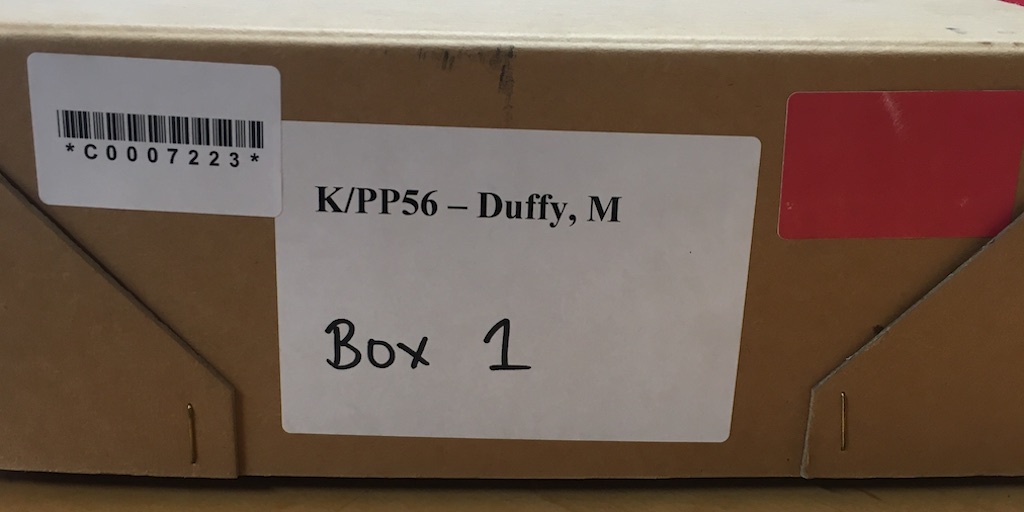

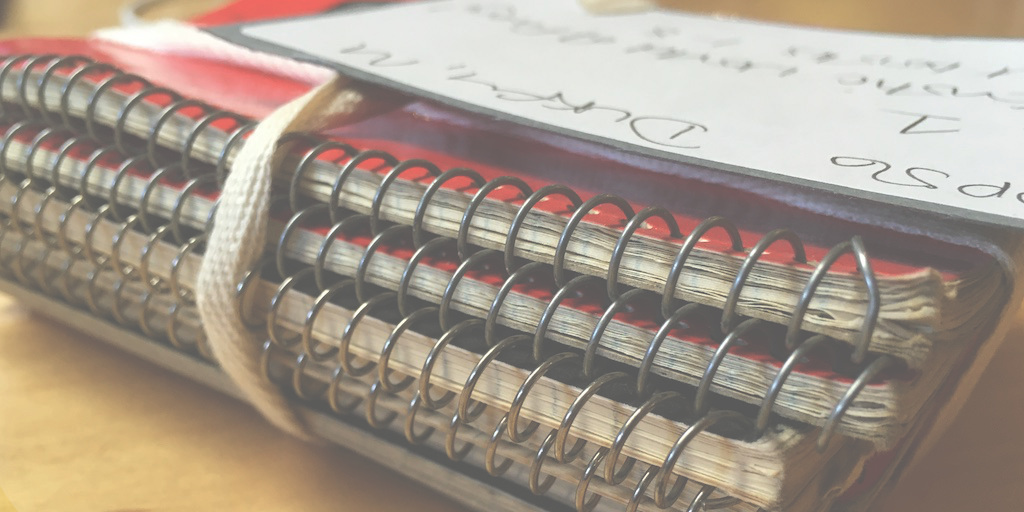

Header image: Maureen Duffy's notebooks in the King's Archives, K/PP56, Box 1.

Finding Maureen Duffy in the King's Archives

by Patricia Methven

Introduction

My connection to Maureen Duffy goes back over thirty years when, as a tyro archivist, I went to Maureen’s flat in Brompton Rd in 1981 following her request that she would like to discuss placing her archives in the College. This followed a willingness on the part of the College Librarian to purchase her manuscript of Capital, in which the College is readily recognisable, at a time when Maureen was in need of funds. From the first resulting deposits, Duffy’s archives at King’s have grown to over 100 boxes regularly transferred as Maureen has completed publications or found time to sort materials relating to her wider activities [ed note: now in 2020, 140!]. The most recent material relates to her rights campaigning. There is more to come.

To give some shape to this talk I set myself the notional working title of ‘Finding Maureen Duffy in the Archives’ and propose to cover five themes: ‘what the College Archives tell us’, ‘the imperative to write’, ‘evidence of working methods’, ‘the genesis of ideas’, and ‘rights’ or ‘why writing matters’.

I will start with the College Archives themselves to give some context to the King’s connection.

The College Archives

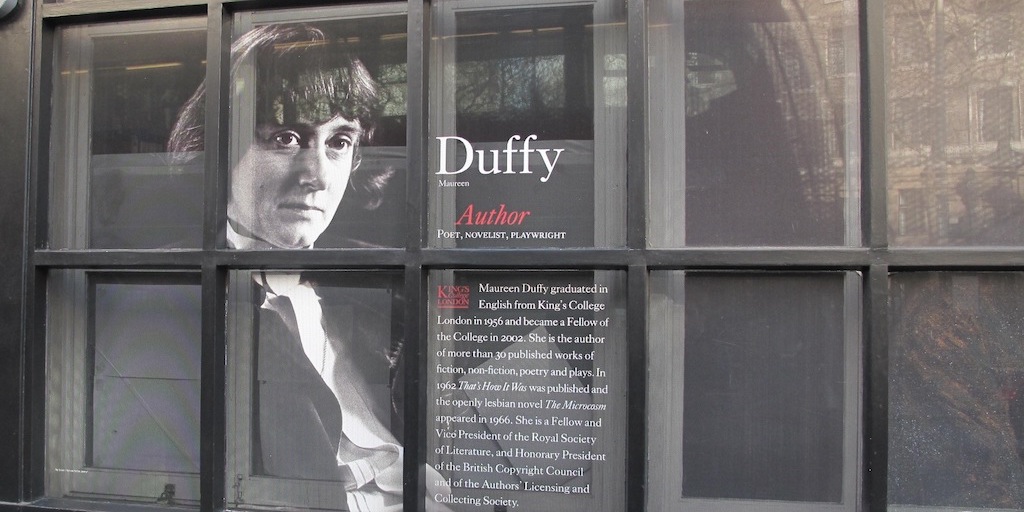

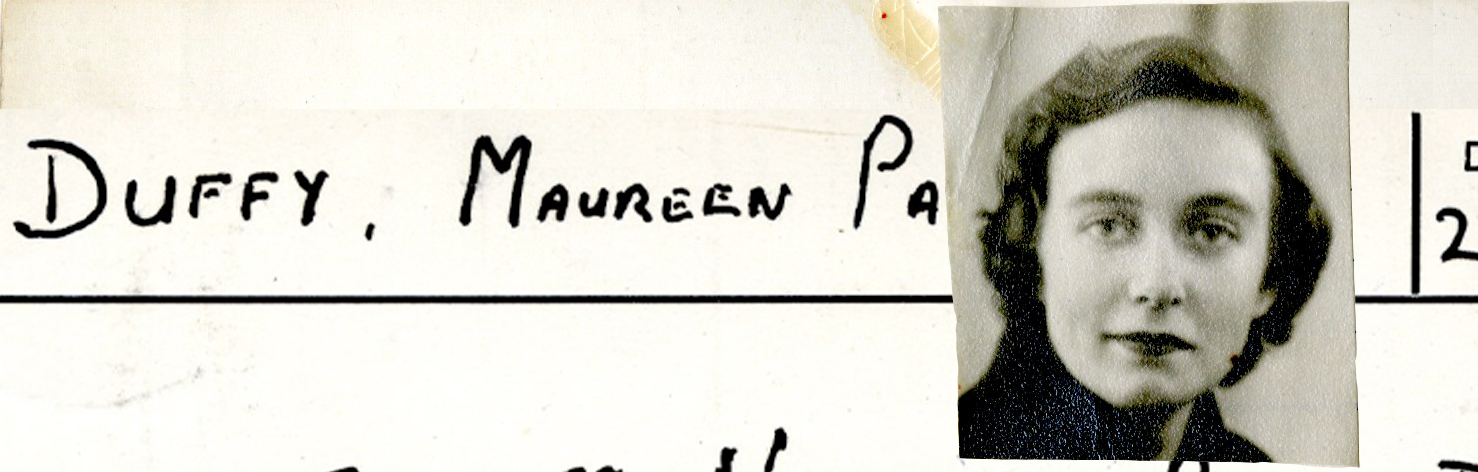

In the exhibition in the foyer there is a picture of Maureen Duffy with softly waved hair swept off the face looking gently into the camera. It is the photograph attached to her official record card which gives the bare bones of the connection:

- Date of entry (1953)

- Date of birth

- Blackheath address

- Education at Sarah Bonnell Grammar School (1948-81), achievement of Advanced Latin, English and History, and study of French

- Award of a London County Council full scholarship (fees and living)

- Successful completion of a BA (Hons) English

- Successful competition of the Associateship of King’s College London - a unique additional course of study on religion and ethics.

Maureen’s record card also notes that she had previously taught at a junior school as an uncertified teacher and includes her interest in folk dancing.

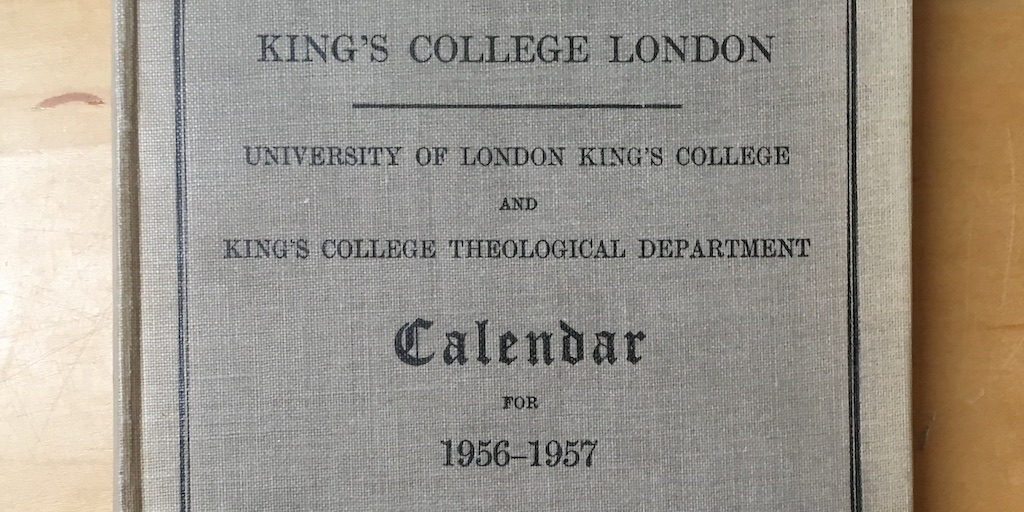

What was the College like that she joined? Small by comparison with today – under 3000 students – but with 30 students in each year on the BA English course. [Editors' note: read more about King's during Duffy's time in Christine Kenyon Jones' contribution].

Post war, the College had a reputation for conservatism with a small ‘c’. Its relationship, as it has often been since, with the National Union of Students was uneasy with a voiced concern that political campaigning should not be prioritised over student welfare. Like the rest of post-war Britain, King’s was changing. The Pacifist Society flourished. Funding in 1954 focused on raising money to support the study of medicine by black South African students otherwise denied support. The dinner at Claridges before the Commemoration Ball was abandoned but the support for the East End Lions Club for boys which offered support for sports and learning continued.

There was also a fair degree of innocent student silliness; my favourite of 1956 being a proposal to establish a Camel Racing Club with camels housed in the Kingsway subway, a uniform of duffle coat, crepe shoes, tight breeches, the College Scarf, with half College colours awarded. The idea was abandoned due to a lack of available training expertise. There wasn’t much support for the idea of a television in the Students’ Union… ‘Watching television,’ the minutes opined ‘was anti-social’. Middle Class students were assuredly the majority, but dramatisations of Rosalind Franklin’s life that suggest a climate of unusually aggressive sexism on the part of the staff at the time are overdrawn and inaccurate. King’s reflected the society of its time, no more or less.

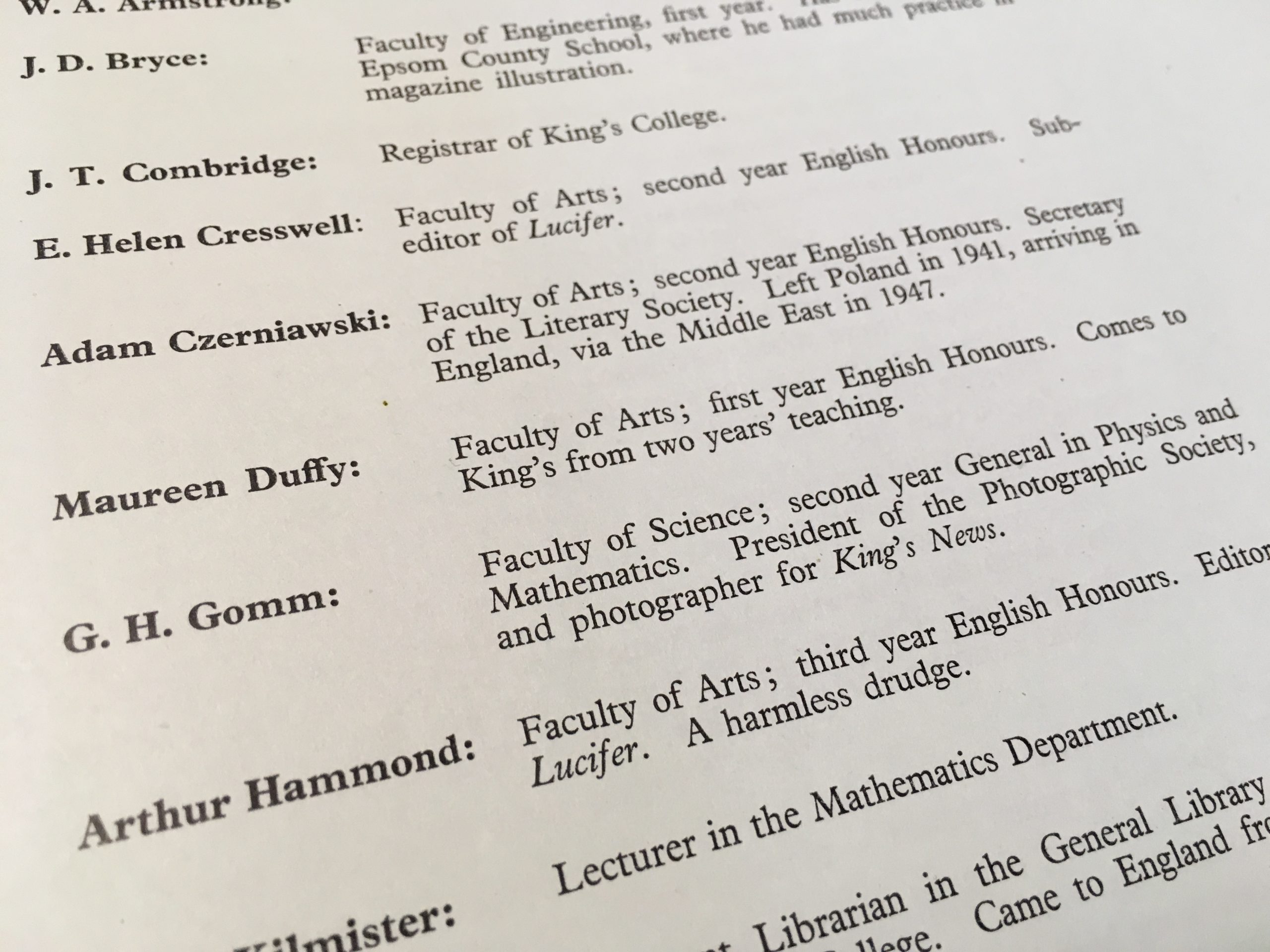

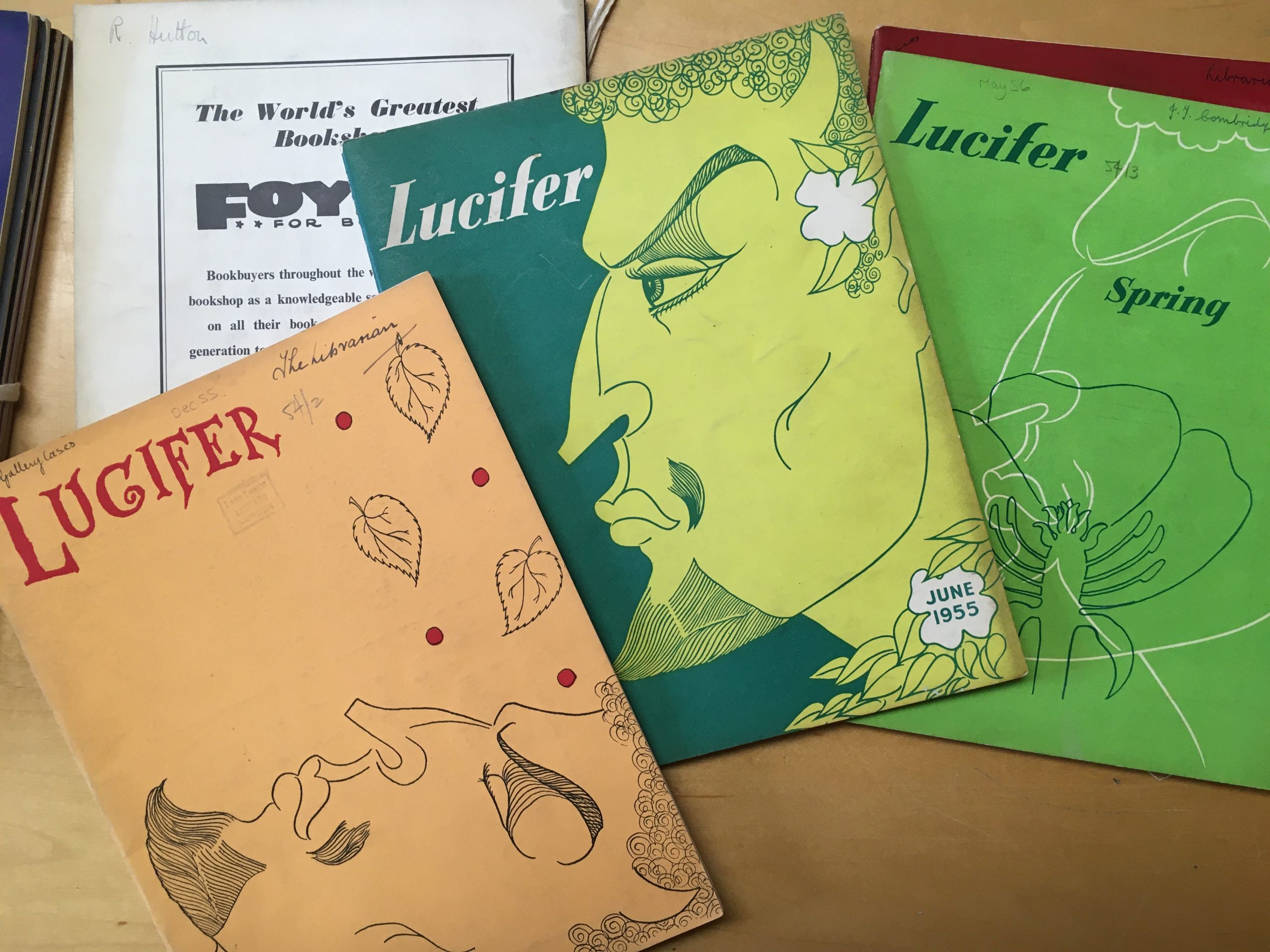

How did Duffy react on arrival - diffident, reluctant to engage? No. The Union Society Handbook of 1953 includes a brief description of Lucifer (The King’s College Review) which had been published since 1899 as a literary magazine ‘whose value and interest depended on the ability of members who contributed to it’. Lucifer enjoyed quite a flowering in its contributors around this period: with Derek Jarman also appearing in the masthead.

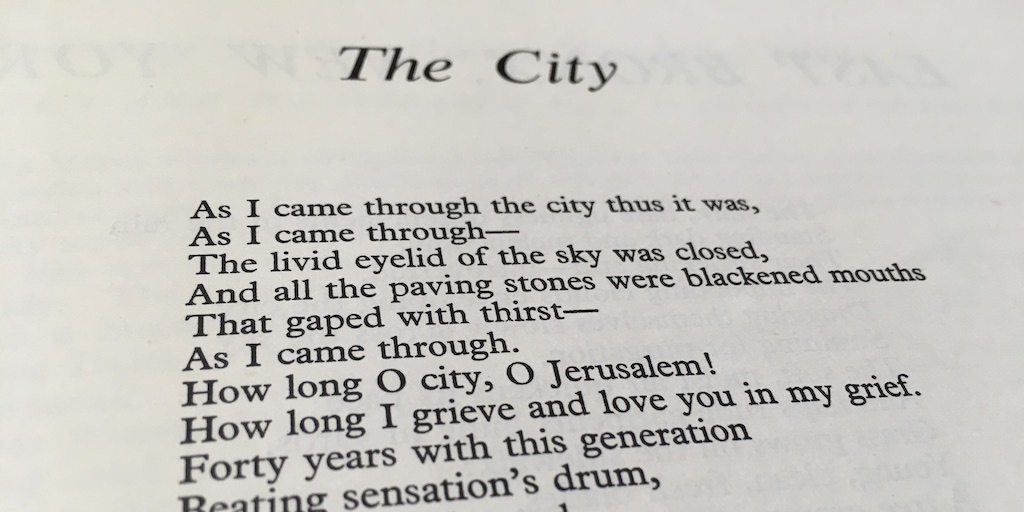

In December 1953 (the first available edition since she had joined the College) Duffy was in print with poems. Most subsequent editions included her work and for a while she was also a sub editor. Whether all of Duffy’s submissions were included or whether they reflect the editor’s selection is not clear. Whichever, they fitted in well - elegant treatments of classical and religious themes, a celebration of Spring and gentle reflections on dead poets and an absorbed old lady in a park.

More trenchantly, in a Students' Union meeting in November 1954 Miss Maureen Duffy is recorded as pointedly asking just how many tickets were available for students for the Commemoration Ball and complaining ‘that 153 double tickets was ridiculously small in view of the College’. She also complained of the method of selling and triggered an investigation. But above all King’s gave Duffy space to focus on her writing and in March 1955 a sonnet published in Lucifer seemed to sum up her mood and offered the confirmation of her vocation:

'Forgive me if today my proud head climbs

The unsteady pinnacle of trust, that is

my time to sing

We shall play tragedies another day'

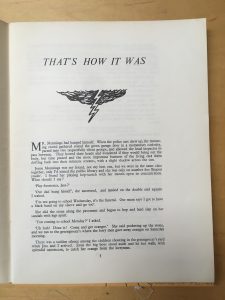

Her last offering to Lucifer in March 1956 reflected that confidence and an ability to draw on difficult lived experiences - a short story entitled ‘That’s how it was’, the only prose piece published which began brutally ‘Mr Munnings hanged himself’. Later it was to be reworked and embedded in the semi-autobiographical novel of the same title. It focused on the undemonstrative respect and space children accorded to the bereaved child of Munnings and the narrator’s gut-wrenching fear of loss of her own mother. It drew on the loss of her own mother to tuberculosis while she was still at school.

The imperative to write

In a text in the Duffy archives, ‘Notes about “That’s how it was”’, and an afterword to The Microcosm written in 1988, Duffy reflects on finding her vocation as a poet and writer, and the influence of her mother.

Evacuated together to Trowbridge during the Second World War Duffy came from a family widely stalked by tuberculosis and where education beyond the strictly practical was uncommon. Life in her family could, she wrote, be nasty, brutish and short. Her mother had a very clear view that education was the way out and, if money was tight, education was prioritised.

Duffy was in no doubt that winning a scholarship to Trowbridge High School was of paramount importance. (She did). Although the school was a different world she embraced it fully and received encouragement to write poems and short stories. When Cecil Day Lewis visited, read and took questions she was clear that she wanted to be a writer or poet, probably a poet, and tells how she spent time in a dream world, much of it impersonating John Keats. Her family concluded she didn’t live in the real world: Maureen writes that ‘For them the sirens’ song that I heard was an unintelligible jangle’. Although Trowbridge offered few opportunities to attend professional stage performances (three in her recollection), those she attended transfixed. They weren’t diversions. They were real experiences of the mind.

Returned to London aged 15 and a pupil at Sara Bonnell, Maureen seized the opportunities the metropolis offered. She heard opera, saw ballet, visited the Tate, the National, the fortnightly pre-Littlewood rep at the Royal, Stratford, because, ‘West Ham Education paid for the Borough’s children to stay in the sixth form and was also paying for me to be fostered.’ As soon as the Royal Festival Hall opened she was there. ‘I can still feel the excitement engendered by the woodwork and glass on the river, by carpets and muted tones announcing that the music was about to begin…’

It is reflections such as these that are included and inform her spirited defence over time of the Arts Council’s work and the significance of sustained free access to libraries. They also underpin the commitment she gave in a stint as an artist in residence at Newbury Library where instead of confining herself to the gallery space she ran Saturday writing classes, offered individual consultations and got out and about in the borough.

Working methods

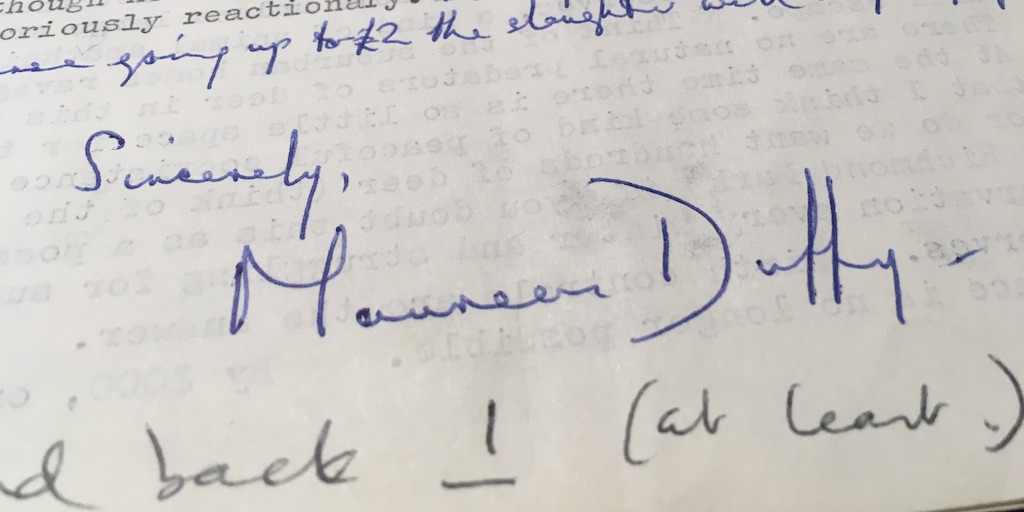

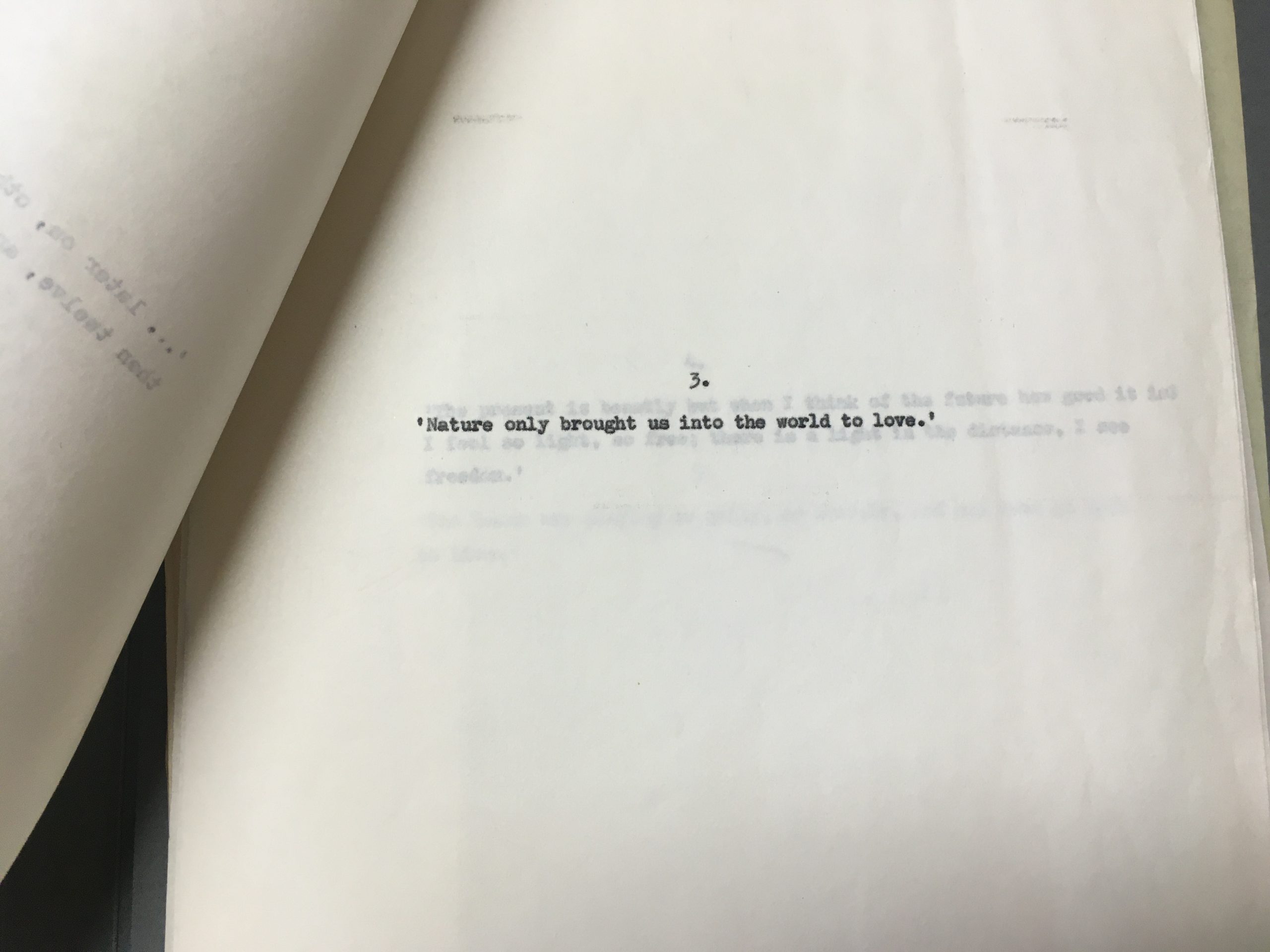

Duffy doesn’t keep everything, but if what we have offers an accurate reflection (and I have no cause to doubt that it does), it testifies to a very ordered mind. Typically for monographs, novels and non-fiction, she writes on a single side of lined paper - initially spare London County Council school exercise books and in pencil, and later on WHSmith A4 pads in ink. The reverse is kept for insertions and corrections. Retained pad pages are tied together with string or tape, the whole given a title, date and paginated.

The evolution of a text may be illustrated by The Erotic World of Faery. For this there is a two-page list of chapter headings and indicative contents. (For other texts there are one-page treatments for use by her agent). For Faery the list of 15 chapters runs through origins and psychology, the conscious and unconscious, elves-medieval literature, Oberon and Titania, Elizabeth I, Paradise Lost, Magic Flute, Swift’s Little People, Bunyan, CS Lewis, and eventually to Ray Bradbury and Disney. This is a much-abbreviated version. It is backed by eight tiny Smith’s ring binders divided by broad subject areas with quotes, references, ideas, notes to look up, years and events, all captured again on single sides to allow for insertions.

Beyond these there are the exercise books or the pads and instructions to a professional typist to produce a top copy and number of carbons, corrected typescripts sometimes and perhaps further annotations. There is less evidence of the physical genesis of the poems but long hand manuscripts in ink and carbons typically exist as do clear titles and dates. There is not evidence of versioning or abandoned fragments. Plays and reviews reflect a similar transition through long hand, typescript, proof and published version.

Before I move to another theme, and in reference to Faery and as something of a sidestep, I wanted to share an example of a typically trenchant review. Considering lone and Peter Opie’s ‘Children’s games in the street and the playground’ Duffy welcomed the substance and record but questioned whether the text also pandered to the typically generational tut-tutting about kids gone soft then typified by HE Baker. ‘He should have come down our street. We’d have shown him’ she wrote tartly before pointing out that the best games played in the street were played away from adult eyes, and how location, for instance rough ground, could have a transformative effect. More deeply she wanted more from them on the imperative of pretence, the fey. The record was OK but what does it really tell us? Maureen had doubts about what the Opie record could really tell us.

The genesis of an idea

At the heart of much of Duffy’s work is often a question - a need to discover - typically followed through by deep research and a willingness to challenge comfortable orthodoxies or lazy thinking.

The Microcosm began as questions about the impact of the sixties and the sexual revolution. Had it made a difference? How had it been experienced? Across a broad demographic Duffy interviewed women and wrote a treatment for a monograph for her agent to promote. The treatment failed to find a publisher, but Anthony Blond offered lunch and subsequently £15 per week for as long as it took to provide a novelised version. The money was attractive but a novel? When the school syllabus moved from Walter Scott to Austen and the Brontes Duffy has described how she had given up on cosy novels for ladies with time on their hands. Yes, the discovery of Woolf and the two Joyces, James and Cary, commanded her personal respect but ‘lady novelist’ was not a term of respect.

Nevertheless she described the ‘rush of adrenaline that comes with a new idea’. Rejecting Blond’s money, Maureen went with another publisher, Hutchinsons, and decided that if she was going to go with a controversial subject she might as well experiment with the structure as well. One critic commented that The Microcosm was ‘wilfully experimental’. She took it as a result! The work found an audience with letters pouring in from women thanking her for the first published reflection of their experiences. She did not keep the letters. It is a pity.

Aphra Behn sprang another enquiry. Virginia Woolf had written that ‘we should all be grateful to her and strew flowers on her grave’. Who? Where? Why? Duffy had never heard of her and sought to find out more. Of The Passionate Shepherdess, one reviewer commented, ‘The sheer amount of detail that Duffy unearths successfully dispels any remaining qualms about Behn’s professionalism - her general refusal to compromise on plot and theme demanding to be considered poet first, woman second…’. Curiosity sated, the reappraisal delivered, Duffy concluded that biography could be delivered with honour. She was also to find fellow feeling with Behn ‘forced to write for bread and not ashamed to own it’. This leads me to…

Rights or writing matters

You have already heard of Duffy’s engagement in the Writers Action Group, Public Lending Right (PLR), Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society, Writers Guild and beyond to the British Copyright Council and campaigning on IPR and the European Copyright Directive [ed note: see 'Maureen Duffy: Fighting and Writing']. The Archives reflect that engagement richly; the letter writing campaigns with Brigid Brophy for PLR and also animal rights (originals and responses), letters to the press (including accusations about the doctrinaire views of editors), published and informal reports, records of court cases and legal opinions (including some with the English carefully corrected by Duffy), campaigning literature, minutes, position papers, conference papers, talks and more.

For historians of rights and anyone wishing to understand the position of the creative writer in particular they are gold dust in their detail and reflection of networks. They testify to a determination not to be bowed and an appetite to speak out as Duffy’s active roles as President of Honour for various groups continue to demonstrate. The attention to detail, as in other work is clear.

In defending rights, she and Brophy wrote personal letters that evidenced some careful steerage of positions and a determination to ensure that writers’ rights, not political positions, remained the key focus. When, however, Universities UK and the Copyright Licensing Agency fell out over rights Duffy was not reluctant to stand for the interests of writers who lacked the security of an academic post.

Why this focus? Duffy, as all speakers have remarked, is passionate about the craft of writing and is clear that writing, as a profession, is significant. In 1981 in a conference paper and in reference to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights she noted that the attainment of rights often entailed writing and that literature gave voice to dissent - political, social or religious. She cited The Rights of Man, A Day in the Life…, and The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist by way of evidence.

Duffy discussed how Article 19 was about freedom of expression and opinion. Censorship of work, whether exercised by repressive regimes, moral codes, editorial decision or fashion risked a fundamental undermining of that freedom. Article 23, she observed, focused on how everyone (including writers) had a right to equal pay for equal work and remuneration sufficient to sustain an existence of dignity.

In 2005 as President of the European Writers Congress Duffy returned to the theme of intellectual property rights as fundamental rights, commenting that they had been recognised in common law for centuries and by the common sense of fairness and ordinary members of the public. She continued to oppose strident and overambitious campaigning by writers as a ‘self defeating punitive road’ but was equally clear ‘That without the nourishment of economic support, the child (the writer) will not be able to flourish’.

Find more of Duffy in the Archives

What I covered does no more than give you a flavour of the richness of Maureen Duffy’s personal archives and context within King’s College London Archives but I trust I have shared enough to encourage at least some of you to visit, to explore further and to find or develop further your own understanding of Maureen Duffy in the archives.

Sections and Chapters

Duffy and King's introduction

Katie Webb

Finding Maureen Duffy in the Archives

Patricia Methven

King's in Maureen Duffy's time

Christine Kenyon Jones

Kings, and Queens, Histories in Fact and Fiction

Clare A. Lees

Panel Summary: the city as a space for new possibilities

Phoebe Blatton

Writing, Rites, and Rights

John Stokes

A Window for Maureen Duffy

Clare Brant

Fighting and Writing introduction

Katie Webb

Duffy and the European Writers' Congress

Lore Schultz-Wild

An 80th Birthday Honorific Speech

Ingrid Protze

Memories of the German Writers' Union

Sabine Herholz

On Maureen

Katalin Budai

A copyright warrior and a true defender of rights

Olav Stokkmo

Recognising writers: responses, records, royalties

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy's contribution to gay rights and lesbian visibility

Jill Gardiner

For Maureen Duffy, Poiêtes

Karen Gevirtz

Editor's introduction

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy: Scrivener and Prophet

Charles Lock

Words that count: Maureen Duffy

Marina Warner

Browse articles on Duffy and King's