True harmony and brotherhood

Posted in Strandlines and tagged with

18th century freemasons meeting in and around the Strand

The history of freemasonry as a secular, fraternal organisation in England dates from the late seventeenth century, when several private lodges are known to have existed before four London-based lodges formed the first Grand Lodge in 1717. Another group of masons formed a rival Grand Lodge known as the ‘Antients’ in 1751, after which time the inaugural Grand Lodge became known as the ‘Moderns’ or ‘premier’.

The two merged to form the United Grand Lodge of England and Wales (UGLE) in 1813, with the Duke of Sussex, a younger son of King George III, as Grand Master. This Union represented a period of standardisation, consolidating the basic administrative structure of freemasonry under the English Constitution – which continues to this day.

Whereas others have researched the social, economic and artistic development of the Strand area and its inhabitants using eighteenth century ecclesiastical and civilian archives, to date few scholars have investigated the surprisingly rich resources to be found for this location among Masonic records. Rather than attempting a comparative topographical study of eighteenth century social life on the Strand, this paper aims to provide an introduction to the Masonic presence in this dynamic neighbourhood since 1717 and the archives created by such activities.

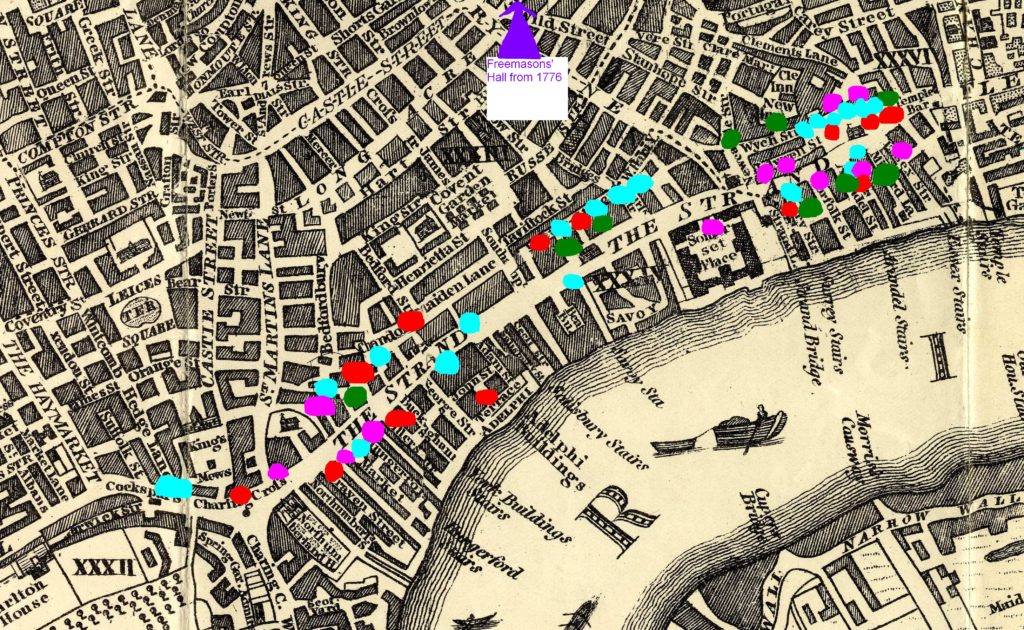

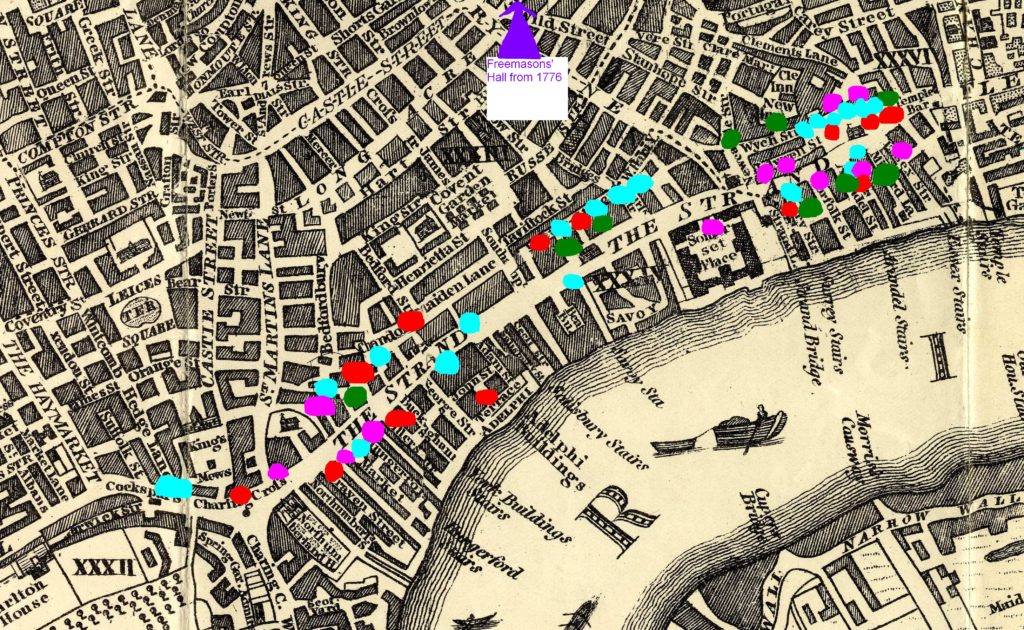

Excerpt from a reproduction of John Evans’ A new and accurate plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark etc 1799, annotated to indicate lodges meeting in premises identified as being sited in or around the Strand between 1725 and 1825. More than one lodge might have met at a single venue over time.

Blue: 1725 – 1749; Purple: 1750 – 1774; Red: 1775 – 1799; Green: 1800 – 1825

Described in Elizabethan title deeds as “the High Street of Westminster, commonly called the Strand,” the area once served as the focus for river fronting mansion houses.[1] Their illustrious owners provided names for the numerous alleys and courts that extended north and south from this narrow thoroughfare today. Tudor residents who have provided names for the many courts, roads and alleyways leading from the Strand include the Norfolk, Arundel, Howard and Surrey families.[2]

Forming a pivot west and east between the cities of Westminster and London, by the eighteenth century the Strand had developed into a community of bankers, shopkeepers, transportation providers, printers, booksellers and traders. It attracted visitors from the theatrical, musical and legal neighbourhoods to the north and from the commercial hub of the River Thames to the south. Its built environment included several almost derelict mansions, numerous narrow Tudor tenements as well as new buildings erected by speculators or provided with updated elevations after the late 17th century Restoration. Many Tudor and Jacobean edifices in and around the Strand survived into the mid-nineteenth and in a few cases into the twentieth century. Into this milieu the four Adam brothers erected London’s first neoclassical housing development in 1768, the Adelphi Buildings, the epitome of enlightenment thought and cultural expression.

To cater for the social and recreational needs of such a diverse local community comprising inhabitants and transient visitors attracted by its various entertainments, numerous refreshment venues appeared in and around the Strand during the eighteenth century. Occupying premises dating from the Tudor period or newly erected buildings, such establishments included Twinings’ tea house and several coffee houses dating from the previous century, in addition to numerous inns and taverns.[3]

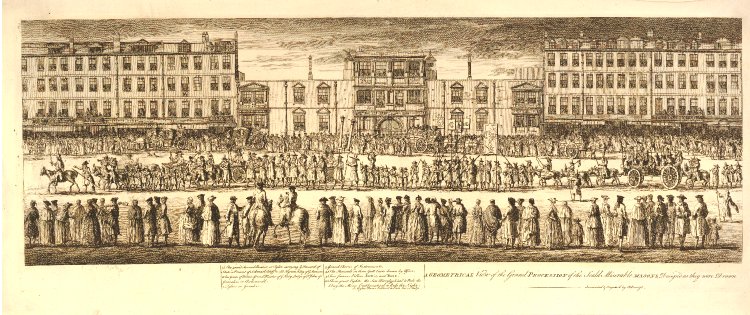

Many premises offering alcoholic beverages expanded during this period to offer comfortable dining and accommodation facilities with private meeting rooms. The development of a sophisticated network of clubs and societies is closely associated with this expansion in recreational premises and social meeting places.[4] These processions were organized by Paul Whitehead and Esquire Carey, surgeon to the Prince of Wales and Masonic Grand Steward in 1740, were held on 19 March, 27 April and 2 May 1741. A print of this procession by Antione Benoist (1721-1770), published in 1771, provides a contemporary panorama of the Strand near Somerset House.

A geometrical view of the Grand Procession – British Museum – Antoine Benoist via

https://www.britishmuseum.org/.

The governing body of the freemasons one such fraternal society, Grand Lodge, met at various taverns along the Strand before the first Freemasons Hall was constructed in 1776. This may have encouraged Lodges meeting under its jurisdiction to emulate it by meeting in similar accommodation in the locality. When seeking a permanent home for Freemasons’ Hall, Grand Lodge disregarded sites near the City or the seat of government at Westminster, eventually selecting Great Queen Street after considering alternatives in Portugal Street, Ormond Street and Fleet Street.

Before building this permanent base, members dressed in full regalia formed an annual procession, preceded and followed by musical bands, from the home of the incoming Grand Master. This parade in honour of the annual Masonic Grand Festival arrived at one of the taverns on the Strand, or one of the City livery company halls after 1721 (and the Twinings’ Devereux Court premises offered refreshment to fashionable London residents from 1710). By the 1730s it was subjected to parody by the Order of Scald Miserable Masons who formed a mock procession along the Strand which hastened the demise of this annual parade in 1747.[5]

Membership of the lodge

The Premier Grand Lodge on Great Queen Street today.

Membership of a lodge was (and is still is) based upon strict moral standards encompassing brotherly love, relief and truth and includes participation in ceremonies incorporating symbolism and role-play, whose costume, drama and ritualistic myth-telling elements continues to attract many members. Such role-play became a feature of many other friendly and fraternal organisations, which often incorporated Masonic iconography to decorate artefacts associated with their material culture.[6] Although many clubs and friendly and fraternal societies have adapted original remits over time, freemasonry remains the largest fraternal membership organisation.

Membership records reveal a surprising diversity among members, especially during the eighteenth century when writers and artists joined alongside members of the Royal family and other aristocrats. In contrast with clubs and coffee houses, which had become a popular activity within the commercial sector during the early eighteenth century, lodge meetings offered members an opportunity to mingle among knights and nobles. The eighteenth century saw a surge in growth in the number of clubs established: from about 150 to over 6,500 between 1700 and 1790 in England.[7]

Whereas the nobility dominated membership of lodges on the continent, membership of English lodges was not exclusive and reflected relative social mobility. This assisted the growth in popularity and respectability of freemasonry – for example during the 1730’s various members of the arts, including the writer and artist William Hogarth and the poet and playwright, Colley Cibber, attended the Lodge meeting at the Bear and Harrow Tavern in Butcher Row, Temple Bar, alongside George Lewis de Keilmansegg and various nobles.[8] As Peter Clark has stated, freemasonry in England unlike elsewhere in Europe during this period ‘never suffered persecution or serious harassment’ and ‘enjoyed the widespread support of the respectable classes’.[9]

In addition Clark calculated that Moderns’ Lodges in London each attracted on average about twenty members in the first quarter of the eighteenth century but by the 1760’s this had increased to c.33 members.[10] These estimates may not always represent unique individuals as members frequently joined more than one lodge.

Strand lodges

A preliminary investigation has revealed that between c.1725 and 1825 at least 57 Lodges met in Strand-based taverns, inns, coffee houses and in one case in a private room at Somerset House (see Appendix 1 – data on lodges meeting in the Strand and adjoining areas is derived from Lane’s Masonic Records on-line database). Plotting known locations for meeting places along and around the Strand provides some early indications that by 1750 most lodges favoured hostelries offering accommodation in Butcher Row or Holywell Street. Several transferred to inns in more refined areas further west by the end of the eighteenth century, before returning to premises nearer the eastern boundary of the Strand during the early nineteenth century. (For a plan see Appendix 2 of Lane’s Masonic Records).

Although Freemasons’ Hall opened not far to the north in 1776, it did not affect the regular pattern of seventeen lodges on average meeting in premises in or around the Strand during this century. After space at the new Hall became available for hire, this was too large for most lodges in the Holborn area that continued to meet in cramped rooms at the adjoining Freemasons’ Tavern.

Additional research using other resources available at the Library and Museum of Freemasonry may reveal details for other lodges meeting in the Strand area.[11] Some met at the same premises for many years whereas others relocated to alternative venues nearby or elsewhere in London. For example, Manchester Lodge met at a succession of premises in the area for over a half a century, including the Crown, Essex Street; the Swan, Butcher Row; the Sun, St Clement’s Inn Foregate, before relocating to the Crown and Anchor Tavern. This last venue, rebuilt in 1790, offered a variety of meeting spaces and formed a popular home for political meetings and several other societies and no fewer than six Masonic Lodges.

Therefore given the membership estimates compiled by Clark from various primary and secondary resources it is possible to extrapolate that during the long-eighteenth century approximately 1,250 members attended Lodge meetings in or near the Strand.[12]

Throughout the eighteenth century, members of a Lodge met usually around a trestle table, with the formal meeting or rehearsals interspersed by numerous toasts followed by a meal in the same room. Soon after the merger of the Moderns and Antients to form the United Grand Lodge in 1813, the format of lodge meetings and ceremonies were regularised. Food, alcohol and tobacco were banned from a formal Lodge meeting and all social dining and entertainment was restricted to what became known as the Festive Board, which took place elsewhere in the establishment or at another venue.[13]

The Premier Grand Lodge on Great Queen Street today, looking east.

Several lodges remained loyal to venues on or near the Strand, some meeting in that locality as late as the mid nineteenth century, before moving to hotels offering exclusive meeting rooms decorated especially for Masonic purposes, known as temples. Despite numerous changes since the eighteenth century members today would still recognise the remarks made at the end of a Lodge meeting that it was closed ‘with feelings of true harmony and brotherhood’.

In conclusion this article aims to raise awareness of the wealth of social and topographical information accessible from secondary and primary resources such as Masonic periodicals, lodge histories, membership registers, annual returns, historical correspondence held by the Library and Museum of Freemasonry. Further research among these resources, yet to be fully exploited by those interested in London’s topographical and social history, is required to uncover further information about eighteenth century Strand inhabitants and visitors.

Susan A Snell

Archivist and Records Manager

The Library and Museum of Freemasonry

Sources

[1] See ‘The Strand: Introductory and historical’, Old and New London: Volume 3 (1878), pp. 59-63 <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45133&strquery=high+street> [Date accessed: 21 March 2011].

[2] ‘The Strand: Introductory and historical’, Old and New London: Volume 3 (1878), pp. 71. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45133&strquery=high+street> [Date accessed: 21 March 2011].

[3] For further information on the social aspects of eighteenth century freemasonry see John Hamill, The History of English Freemasonry (Lewis Masonic Books, 1994).

[4] London’s Masonic Processions and the Patriot Opposition, talk given by Andrew Pink, British Society for 18th century studies conference 2006.

[5] Peter Clark, Chapter 5 Engines of Growth, section IV, in British Clubs and Societies 1580-1800 The origins of an associational world (Oxford Studies in Social History, 2000)

[6] For further information about identifying material culture of friendly and fraternal societies see Discovering Friendly and Fraternal Societies: their badges and regalia, by Victoria Solt Dennis, Discovering Series No. 295 Shire Publications, 2005 ISBN 0747806284 and for additional Masonic degrees, such as Knights Templar, see Beyond the Craft, by Keith Jackson, Addlestone, 4th edition 1994.

[7] ,Chapter 9 Freemasons, in British clubs and societies, 1580-1800: the origins of an associational world, Peter Clark, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2000. See also Politics and Freemasonry in the Eighteenth Century by Aubrey Newman, Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, vol 104, pp32- 50 L&M ref: A 31 QUA fol.

[8] List of members for 1730 Lodges included in Masonic Reprints of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076, London, Quatuor Coronatorum Antigrapha vol 10, L&M ref: A 31 QUA fol. David Bindman, ‘Hogarth, William (1697–1764)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13464, accessed 31 Jan 2011]; Colley Cibber junior, 1671 – 1757, Eric Salmon, ‘Cibber, Colley (1671–1757)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5416, accessed 31 Jan 2011]; George Lewis de Kielmansegg (Georg Ludwig Graf von Kiely), 1705 – 1785, eldest son of Sophia Charlotte, half-sister of George I, former Elector of Hanover, and Johann Adolf, Baron von Kielmansegg, Deputy Master of Horse to George I. A soldier, Georg took part in the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War and was present at the initiation of the future King Frederick II of Prussia at Brunswick in 1738.

[9] Peter Clark, British clubs and societies, 1580-1800: the origins of an associational world, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), p. 312.

[10] Peter Clark, British clubs and societies, 1580-1800: the origins of an associational world, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), p. 310.

[11] Further research among other primary and secondary resources in the collections of the Library and Museum of Freemasonry, such as annual returns of members to Grand Lodges, membership registers, printed lists of lodges, lodge histories, historical correspondence, lodge minute books (Often in the custody of the lodge if still meeting) etc, as well as searching meeting locations in all the courts and streets joining the Strand in Lane’s Masonic Records, would reveal details for other eighteenth century lodge meetings places.

[12] Peter Clark, British clubs and societies, 1580-1800: the origins of an associational world, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), p. 310, with particular reference to footnote 7.

[13] John Hamill, ‘Chapter 5 The Social Side’, The History of English Freemasonry (Lewis Masonic Books, 1994), pp. 90-91.

[…] Masonic temple (presumably supposed to lie beneath the Grand Lodge on Great Queen street, the history of which you’ll find detailed in a Strandlines post by Susan Snell) and the British Museum’s Egyptology section (cue droll allusions to the original Tomb […]