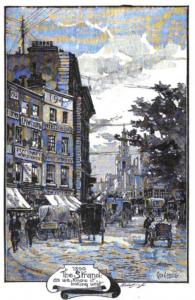

‘The most interesting street in the world’

Posted in 19th Century, Strands and tagged with 19th Century, Fanny and Stella, History, London, Strand Magazine, theatres

The first ever issue of the Strand Magazine was published in January 1891. Its opening sentence informs the reader: ‘The Editor of the Strand Magazine respectfully places his first number in the hands of the public’.

In its inaugural issue, the magazine plays on the place of London’s Strand in the popular imagination as a site of history, culture, and collective memory. In its first feature, the magazine seeks to contextualise the Strand’s place in public consciousness with a foray into the street’s history entitled ‘The Story of the Strand’…

The Strand is a great deal more than London’s most ancient and historic street: it is in many regards the most interesting street in the world. It has not, like Whitehall or the Place de Concorde, seen the execution of a king; it has never, like the Rue de Rivoli, been swept by grape-shot; nor has it, like the Antwerp Place de Meir, run red with massacre. Of violent incident it has seen but little; its interest is the interest of association and development.

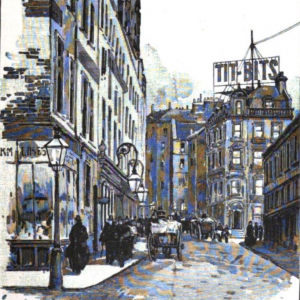

So this magazine, which ran until March 1950, situates the Strand as a place known not for a single important historic event or as a centre of institutional power, but as a place of people, a street where society coalesces. Now, as in the nineteenth century, the Strand is an important site of cultural and economic exchange, housing as it does educational institutions, hotels, offices, and theatres.

It is not a fine street, and only here or there is it at all striking or picturesque.

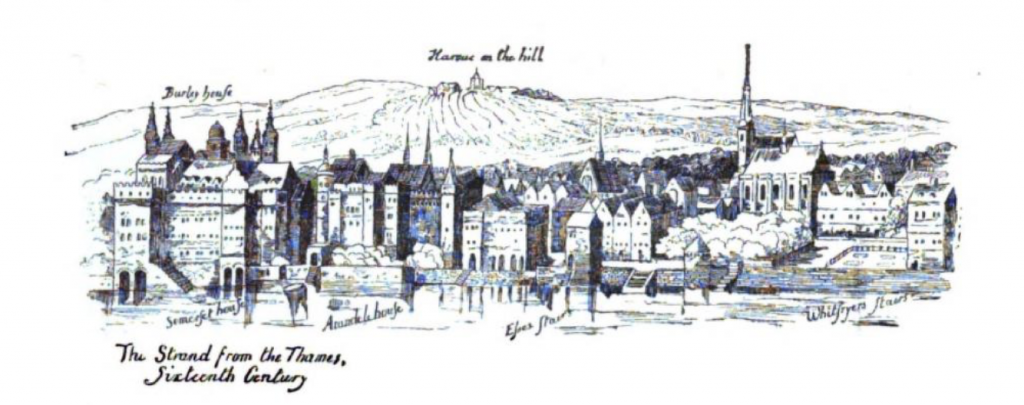

As I flicked through the magazine’s description of the street, I was hunting for the mysterious essence of what makes the Strand such a significant site in the London imaginary. Its position next to the river–it used to be situated right on the riverbank–is one distinguishing feature. So too is its geographic passage which connects the east of the city, St Paul’s and the financial district, with the stately centre of London: Nelson’s column in Trafalgar Square which leads in one direction to the Mall and Buckingham Palace, and in the other down to Westminster and the House of Parliament.

But it’s the less tangible atmosphere of the place that is harder to pin-down. The bustling mix of workers, students, and tourists. Streams of cyclists rush down the recently developed cycle path from Covent Garden. Reckless black cabs weave in and out of traffic, shortcutting down a backstreet. The homeless congregate on a Friday evening near Charing Cross Station, waiting for the soup kitchen. The glittering theatres spill their audiences back out on to the street after every performance; an exciting, surging crowd dissolves into the homogenised mass of city-dwellers, as they have done for hundreds of years.

Twenty years before the Strand Magazine published its first issue, a pair of flamboyantly dressed women were arrested after causing a scene at the Strand Theatre. Fanny and Stella, otherwise known as Thomas Boulton and Frederick Park, were a pair of cross-dressers charged with ‘conspiring and inciting persons to commit an unnatural offence’. This euphemistic phrase refers to the act of anal sex, but as the prosecution were unable to prove this, and since dressing in women’s clothing was not itself a criminal act, both parties were acquitted. As a theatrical double act, Fanny and Stella gave performances and frequented West End theatres in drag. It’s hard to imagine not being delighted by the exuberance of this amusing pair.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the Strand is its capacity to hold so much life, so many sorts of lives. The Big Issue seller who bravely interrupts busy walkers, enticing them to stop for a chat, or at least smile as they pass. The commuters who spill back and forth over Waterloo Bridge. The tourists who gravitate upwards towards Covent Garden. The buses which flow through the arteries of the city. It is a street which has changed beyond recognition and yet somehow, not changed at all.

It would be impossible to find a street more entirely representative of the development of England than the long and not very lovely Strand. From the days of feudal fortresses to those of penny newspapers is a far cry; and of all that lies beneath it has been the witness. If its stones be not historic, at least its sites and its memories are; and still it remains, what it ever has been, the most characteristic and distinctive of English highways.

Images: Original illustrations from Strand Magazine (January 1891).