Arundel Great Court: between redevelopment and conservation

Posted in 1980-1989, 2010-2019, 20th Century, Architecture, Places, Strandlines and tagged with Architecture, Arundel great court, brutalism, demolition, gibberd, mix-use, redevelopment, strand, Town planning, urban design, Westminster

180 Strand, the remaining part of the former Arundel Great Court, is located between Somerset House and the Inner Temple. Constructed between 1971 and 1976 the building stands as a brutalist landmark in the heart of the Strand. Once a multi-use office space, now an art and fashion hub, the site will soon be redeveloped and transformed.

Medieval beginnings

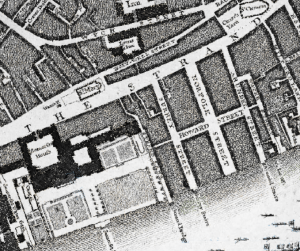

Arundel Great Court was built following a commission to replan a full street block, on the former site of the Bishop of Bath and Welsh Inn, granted to Eustace de Fauconberg in 1221. Under the reign of Henry VIII, the palace lost its episcopal function and then frequently changed names: in 1539 it became the Hampton Palace, in 1545 the Seymour Place.

After 1549, it was purchased by Henry FitzAlan, 19th Earl of Arundel, who gave it its final name of Arundel House. This house was demolished between 1680 and 1682 but gave its name to the street where it used to stand.

Williams Morgan Map of the city of London, Westminster and Southwark (1682) British Library

John Rocque’s map of London, Westminster and Southwark (1746) Patrick Mannix/MOTCO

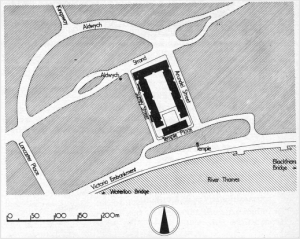

Location plan, Frederick Gibberd and Partners, London (1976) Architects Journal Buildings Library

A 1970s brutalist behemoth

Leaping forward two centuries, Arundel Great Court was completed in 1976 by Frederick Gibberd (1908-1984), an architect and town planner known for his design of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, the London Central Mosque and Harlow New Town.

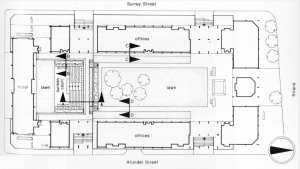

Site plan (1976) Architects Journal Buildings Library

The 54,905m2 complex recovered a 3.3-acre site between Embankment and Strand and was composed of five buildings, facing the Strand, Surrey Street, Arundel Street and Temple Place.

These separate blocks were linked by vertical circulation towers and formed a quadrangle with a central garden inside. Initially designed to be opened to the public, the landscaped courtyard was rapidly shut off. This courtyard element, as well as the scale of the complex, was meant to mirror other palaces of the Strand such as Somerset House and the Savoy, in order to better integrate the brutalist complex to its surroundings.

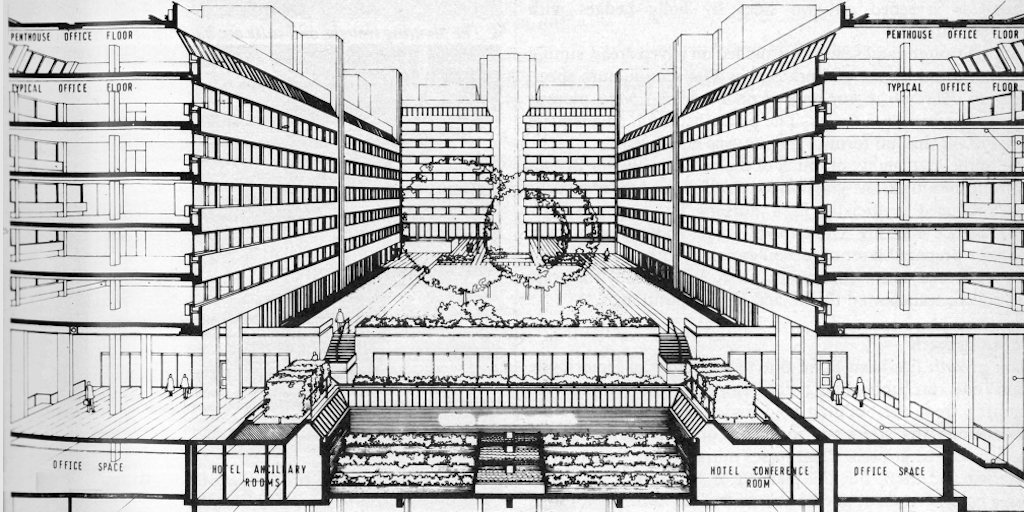

Michael Reid, General view of upper main area (1976) Architects Journal Buildings Library

Arundel Great Court’s bold shapes, largeness of scale and massive character makes it typically brutalist. Indeed, the complex fully corresponds to Reyner Banham’s (1922-1988) definition of the style in The new brutalism (1966): “In order to be brutalist, a building has to meet three criteria, namely the clear exhibition of structure, the valuation of materials ‘as found’ and memorability as image”.

Michael Reid, General view of the upper main area, Architects Journal Buildings Library

Arundel Great Court’s minimal design consists of a simple geometric architectural form: restrained horizontal lines repeated across the complex with rhythm change brought by the vertical articulation of the different blocks.

To complement the complex’s aesthetic simplicity a limited material palette was chosen: Portland stone and bronze finished aluminium windows. According to Muriel Emanuel, the building’s monumentality, rectangle shape with horizontal emphasis and variety brought by patterning fenestration are common traits of Gibberd’s works.

The Arundel Great Court was a mixed-use complex, mostly made up of offices laid out in the building’s unobstructed floor plan. The complex also included small retail units on the Strand end, as well as the Swissotel ‘The Howard’, located at the Temple Place end, that offered a panoramic view of the River Thames until its closure in September 2011.

Teresa Borduka, Above view of Courtyard, Architects Journal Buildings Library

Criticism of the new building

The Arundel Great Court was supposed to embrace modernist ideals. However, it was highly critiqued and was even nicknamed ‘the Arundel not so Great Court’ by londonist.com. Critics claimed that the construction damaged the Strand by erasing a part of its history. After all, the giant complex replaced three ancient streets and the house where Tsar Peter the Great had once lodged.

The monotone design was judged obsolete, and on 4th March 2009 Mayor Boris Johnson officially approved the demolition of all its buildings to make redevelopment possible. This decision reflects a larger tendency towards the demolition of brutalist buildings in England. Media and public resentment rose against the style that was increasingly associated with totalitarianism and suburban housing estates where the poorest were forced to live in buildings whose materials aged ungracefully.

In 2012, Land Securities sold Arundel Great Court for a headline price of £234 million to Waterway PCP Properties Ltd. A planning consent was signed for three asymmetric towers overlooking the Thames: two residential ones with 147 private apartments and a hotel designed by Horden Cherry Lee, on the south side. Despite referencing the Gibberds horizontal line design, the steel and glass style of the future buildings appears quite generic.

The multi-use nature of the original building is kept, as retail space and a 398,000 ft² office building designed by Wilkinson Eyre are also planned. The new development will also conserve the ‘palace-like’ plan of its predecessor with a central public courtyard, arcades and colonnades. We can wonder if Londoners will embrace this space and make it their own or if it will be a space simply dedicated to retail and consumption.

Following this plan, the south end of Arundel Great Court was demolished in 2014 and the new build is currently under construction.

Arundel Great Court, The Strand, by Frederick Gibberd & Partners (11/09/2016) @victorlacima on Instagram

Arundel Great Court is under demolition (2/03/2015) @myromanapartment on Instagram

Changing fortunes

In the last few years, brutalism has however made a surprising “comeback”. The radical functionality and visual impact of these buildings are newly appreciated and brutalism as a whole went through an unlikely revival thanks to the publication of picture books such as This Brutal World by Phaidon. Meantime, on Instagram #brutalism has over 770,000 images and accounts like Brut Group have over 300 000 followers. Admirers of the style even formed conversation groups and took action via databases like SOS Brutalism to preserve this part of 1960s-1970s history.

The North End part of the Great Arundel Court has indeed been preserved for “its heritage” and the support it brings to “its living, working and visiting population” according to Westminster Council. The building’s interiors were stripped and were repurposed as an artistic hub by property developer Mark Wadhwa.

London Fashion Week Men’s Strand (January 2017)

Gibberd’s architecture lends itself to a flexible use of space. Creative director Alex Eagle explains ‘The drama of the architecture, and the scale of it, form the perfect backdrop for an ever-evolving space”. The building hosted the publisher Dazed and Confused and since 2016, The Store X and 180 Strand have been curating the building’s art programme made of talks, screenings, live performances, independent exhibition as well as exhibitions in collaboration with Hayward Gallery, the Friez and Serpentine galleries and more recently Fondation Cartier Pour L’Art Contemporain.

These exhibitions are usually intimately linked to the architecture of the space. The bunker-like nature of the space permits large scale art installations and the cavernous aspect of its stairwells, corridors and basement are used to create surprising and immersive experiences.

Transformer: A rebirth of wonder (2019) The Vinyl Factory, The X store

From simple “Somerset Sidekick” in 2009 according to Lauren Milligan’s Vogue article, Strand 180 progressively built a name for itself. Indeed, in 2019, artist and critic Professor Theaster Gates at the University of Chicago called it “one of the most important places for contemporary culture in London”. The place that used to be the subject of scorn, is now actively participating in the renewal and reaffirmation of the Aldwych area as a creative and arts quarter. The brutalist north end of the building, following a 2018 decision, is due for a single-storey extension, a symbol of its constant evolution.

The history of Arundel Great Court shows that compromise is possible between complete demolition and dogmatic conservation. It reminds us that some buildings reveal themselves through their interiors and the active rôle they may play in a neighbourhood. Despite its revival, the singular building, unfortunately, remains unprotected as it is still not recognised as part of the Strand’s Conservation Area.

180 the Strand (2018) the Vinyl Factory

Further reading and references

Download comprehensive list of references here, and see below for just a few suggestions!