Who put the Villiers in Villiers Street? Art, culture and élite life on the seventeenth-century Strand

Posted in 17th Century, Strandlines and tagged with 17th century, art, art collector, Charing Cross, entertainments, historical parties, History, London, London history, Masques, Thames, Villiers Street, Westminster, York House

Villiers Street has always captivated me. Linking the Strand to the Embankment, it remains one of the most vibrant walkways in the area and it plays an important part in connecting people to some of central London’s main visitor attractions – historical buildings and palaces, galleries, theatres, cinemas, museums and parks. It has a buzzy feel, with shops, eateries and bars up and down and, until recently, it was always packed with people.

When I worked in Embankment Place in the 1990s, we used to fall out of the office on a Friday evening and head straight over to Gordon’s Wine Bar, a convivial venue which is still very much a part of the street’s social and epicurean landscape. In normal times, you can hear the sounds, smell the smells and see so many of the shades of London life in this bustling street.

Fading memories of fun evenings merge with the distant past to explain why this narrow but important thoroughfare continues to capture my attention. Having researched and written about seventeenth-century Britain before, I have an enduring fascination for the eponymous family that gave the street its name.

Villiers Street as we know it today was built in the 1670s, when the second Duke of Buckingham and former royal favourite to Charles II, agreed to the dismantling of York House on the Strand, on the understanding that the surrounding streets would be named in his honour. At the time of its demolition, York House had been in his family’s hands for half a century and its destruction was part of a land transaction aimed at solving some fairly serious financial troubles. We know a lot about the Villiers family, but rather less about what went on in the house under its ownership and York House’s role as a centre of art, culture and entertainment helps us to imagine elite life on the Strand 400 years ago. This is particularly intriguing, because all that remains of the place today is the iconic Italian watergate on the embankment (see Paul Guhennic’s strand on the York Watergate).

Our story begins in the early 1620s

Anonymous portrait of George Villiers, attributed to the studio of William Larkin, circa 1616, National Portrait Gallery.

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham – and father of the 2nd Duke – was favourite to James I, enjoying unrivalled influence, power and wealth. Having caught the monarch’s roving eye, the young, good-looking and ambitious Villiers rose rapidly through the ranks of the nobility to become the most powerful man in Britain and the king’s ‘sweete hearte’.[1] Think of a modern-day senior political advisor, but with a charismatic personality, ‘the face of an angel’ and great legs – something frequently commented on at the time!

Through royal favour and his own vast patronage network, Villiers amassed great wealth at even greater speed. As well as major roles at court (he held the prime position of Master of the Horse and later became Lord High Admiral), he built up an impressive central London property portfolio, including the purchase of York House on the Strand in 1622. York House, formerly the official abode of the archbishops of that diocese, now became Villiers’ semi-official residence in London – a place where he planned lavish entertainments for kings, foreign princes and ambassadors, using the mansion for ceremonial purposes and choosing to live elsewhere in the capital. Although Villiers wanted to knock down the dilapidated house and start again, he had big cashflow problems, so instead had to make good the existing buildings, using a major donation of raw materials from the king and remodelling the interior under the supervision of Balthazar Gerbier.

Anyone who has worked in central London will appreciate that the sound of demolition and construction is part of daily life, as office blocks are pulled down and rebuilt or overhauled. The area around York House in the 1620s was no different. People walking past the gates of the house would have been able to hear the sound of ‘the ceilings of rooms [being] supported with iron bolts, balconies clapped up in the old walls [and] daubed all over with finishing mortar’, as seventeenth-century labourers noisily rushed to complete Villiers’ work.

A flourishing art collection

Sir Balthazar Gerbier

by Paulus Pontius (Paulus Du Pont), after Sir Anthony van Dyck

line engraving, 1634, National Portrait Gallery.

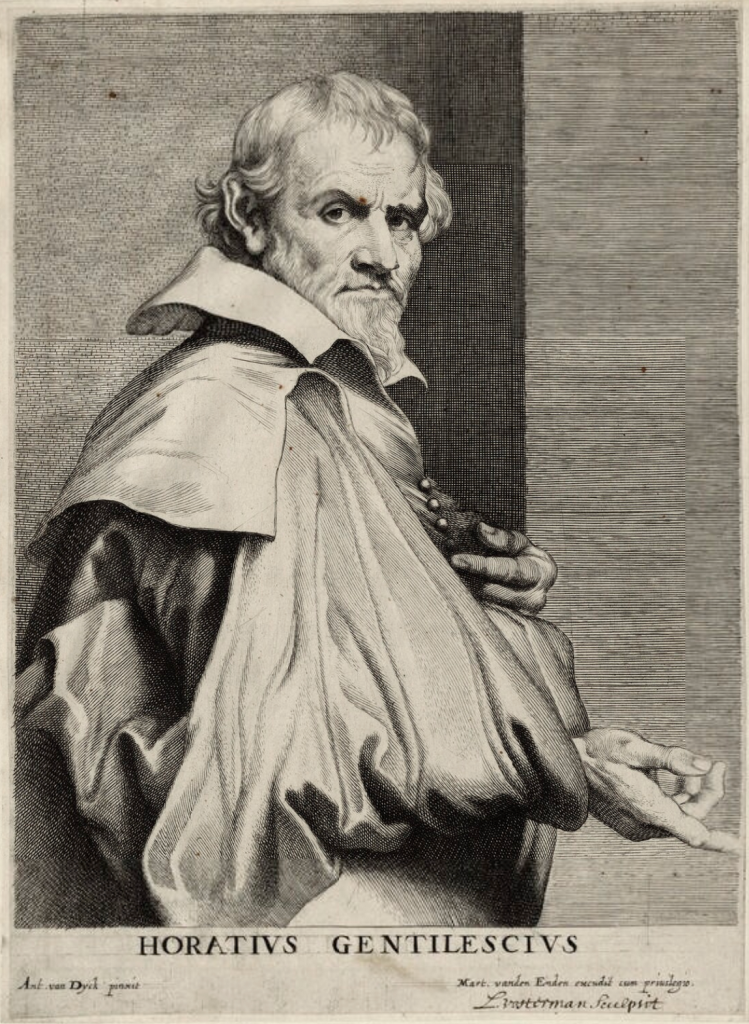

Orazio Gentileschi, by Lucas Vorsterman after Sir Anthony Van Dyck, mid 17th century, National Portrait Gallery.

Gerbier, the project manager of the York House makeover, was an artist and architect of Dutch Huguenot descent who also doubled as a diplomatic agent. Not only did he supervise the renovations at York House, but he also used his diplomatic know-how to acquire paintings and other artefacts for his employer, like many in his position.2

Villiers’ house on the Strand was used as a showcase for his flourishing collection of art by the great masters. The collection was overseen by Gerbier, who was given a place in the household. He was joined by the Florentine painter Orazio Gentileschi, who painted several of the ceilings there, so the place soon became an elite artistic hub. Peter Paul Rubens, later commissioned by Charles I to paint the ceiling canvases at the nearby Banqueting House in Whitehall was a client of Villiers, frequently staying at York House, and it is possibly from here that he prepared his portrait of Villiers, once thought lost, but rediscovered in 2017.

Gerbier was soon effusing his ‘astonishment’ and ‘joy’ that Villiers had managed to create a collection better than ‘amateurs … princes and kings’.[3] Shortly after this enthusiastic endorsement, Villiers’ fortunes further improved when Charles I became king on the death of his father and the favourite achieved the usually impossible feat of not only surviving a change of monarch, but becoming even more powerful thereafter.

The “lost portrait” of George Villiers, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1625, Glasgow Museums.

Marble statue of Samson slaying a Philistine, by Giambologna, about 1562, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Villiers was by no means the only art collector at the royal court but, in their love of art, Charles I and his favourite had something in common. The king’s staggering art collection was and is now internationally renowned and the stunning exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2018 allowed us to see some of his dispersed treasures reunited for the first time since 1649.

What is less widely known is that Villiers himself had such an impressive array of work by the great artists of the age, all within the walls of York House on the Strand. An inventory compiled in 1635 lists 330 works on display there, including many by Tintoretto, Caravaggio, Raphael, Titian, Correggio, Holbein and Bruegel, and the galleries and rooms were adorned with ‘Romane Heads and Statues’ by Rubens.4 The centrepiece of the gardens was the Giambologna sculpture Samson Slaying a Philistine, now in the V&A, gifted to Villiers by Charles I shortly before he became king. Knowing that Villiers had so many masterpieces in his possession helps us to create a mental picture of the interior and exterior of York House as it was then.

A place for parties

Charles I, Queen Henrietta Maria, and Charles, Prince of Wales dining in public by Gerrit Houckgeest, 1635, Royal Collection Trust.

With such an illustrious landlord, the rich, famous and powerful were regular visitors to York House, especially when Villiers himself entertained. Just as he had planned, the house was the venue for extravagant displays of wealth and power when royalty, noblemen and foreign ambassadors were wined and dined in the most magnificent settings, surrounded by works of art in his newly renovated residence. Charles I and Henrietta Maria were known to dine in great style at the house, arriving by barge with their entourages, accompanied by diplomats and courtiers.

On ‘Gunpowder Night’ in 1626, while the royal couple ate, a different ballet accompanied each course, there were frequent changes of scenery, involving waves and clouds and much music. When the meal was over, a grand ballet was performed, in which Villiers himself danced centre stage – something he frequently did at the royal palaces, to show off the ‘daintinesse of his leg and foot’ – followed by further dancing in break-out rooms and the party continued until ‘four in the morning’. The king and queen spent the night at York House, stayed for a ball the next day and went back to Whitehall that evening only after they had watched another dramatic performance put on specially by Villiers. A few nights later, the queen herself hosted a major entertainment further along the Strand at Somerset House, with more ballet, exotic dancing, and food, to which the great and the good were invited. The Strand was right at the heart of royal and courtly entertainment at this time.[5]

Seventeenth-century masque costumes, via Elizabethan Costume.net.

Perhaps the most flamboyant display of artistic power-flexing at York House came in 1627, when Villiers put on a masque for the king and queen, shortly before he left on a naval expedition against the French. Deeply unpopular among the people by this time, Villiers was under constant attack for his excessive lifestyle and botched naval campaigns, but when parliament had tried to impeach him, it failed.

Masques were flamboyant and costly entertainments, involving a blend of music, drama, poetry and dance, with elaborate scenery, special effects and expensive costumes. The élites loved them. Celebrated architect Inigo Jones often designed the sets for the king’s court masques, at which the monarch and his queen performed and no expense was spared. The elaborate masque at York House was no exception, with Villiers performing the leading role. Laughing in the face of his recent political near-miss, he led the performance, followed by a symbolic representation of ‘envy’ as ‘open mouthed dogs’ heads representing the people’s barking’.[6]

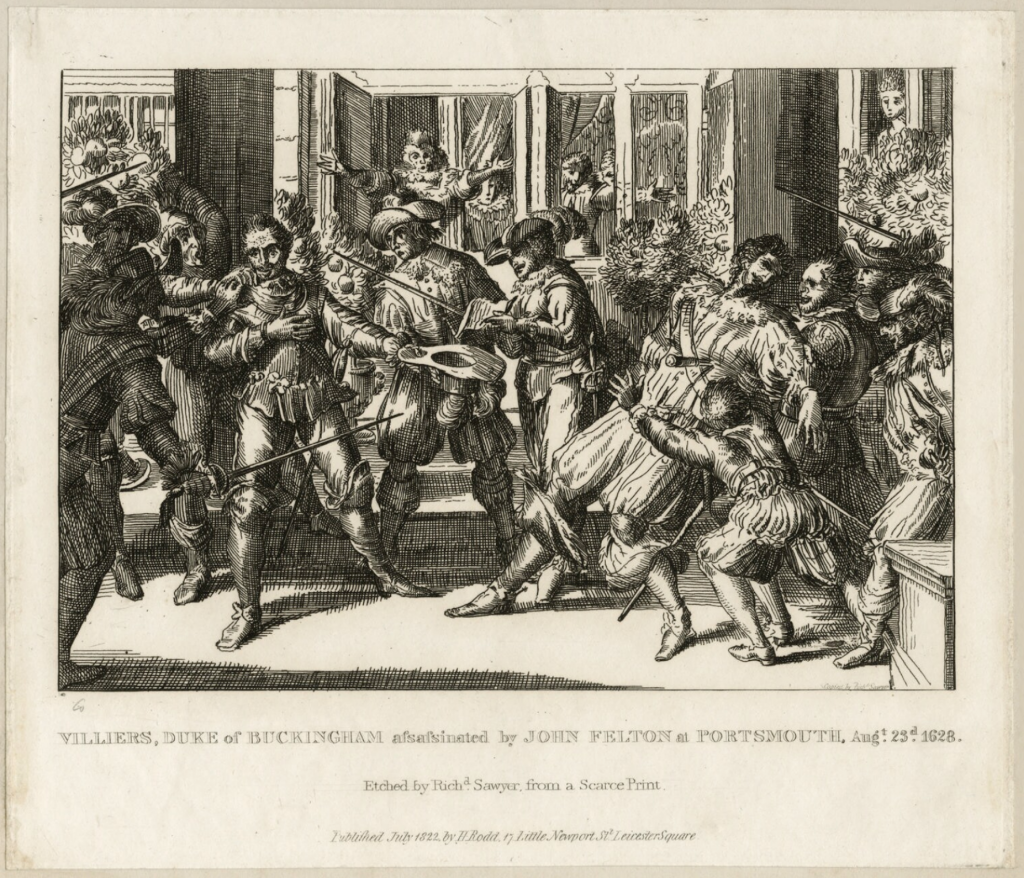

The assassination of George Villiers by John Felton, etching by Richard Sawyer published 1822, National Portrait Gallery.

The dogs came back to bite him the following year, when popular fury against Villiers led to his assassination. Gerbier and Gentileschi continued to live in lodgings near the gatehouse at York House, so the estate retained an artistic studio, but Villiers’ widow soon petitioned to have both men removed. In 1635, when she remarried, she arranged for an inventory of her deceased husband’s art collection to be drawn up, to keep the treasures in trust for her young son, the 2nd Duke. The house and its contents were sold during the Interregnum and only restored to the family in 1660, when the 2nd Duke continued his father’s practice of using the house for hospitality and entertainment.

Of course, we know how the story ends: all that is left of the estate now is the Watergate. When the 2nd Duke finally ran out of money, York House was ordered to be dismantled. The Villiers family may be long gone, but its name is permanently attached to the street which runs alongside where the house used to stand. Perhaps they would approve that the street remains a place of parties and entertainment. Maybe, if he was still around, the Duke would enjoy a drink at Gordon’s before heading to the Piano Bar for a late night dance?

References and recommended reading

1 R. Bentley (ed), The court of King James I by Dr Godfrey Goodman (London, 1839), Vol 2, passim.

2 J. Wood, ‘Gerbier, Sir Balthazar’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, online edn).

3 Bentley (ed), p. 370.

4 R. Davies, ‘An Inventory of the Duke of Buckingham’s Pictures, etc, at York House in 1635’, Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, March 1907, Vol 10, No 48, pp. 376, 379-82.

5 J. Croker (ed), Memoirs of the embassy of the Marshal de Bassompierre to the court of England in 1626 (London, 1819), pp. 92-97; J. McIntyre, ‘Buckingham the Masquer’, Renaissance and Reformation, Volume 22, No. 3, pp. 60, 71.

6 T. Birch (ed), The Court and Times of Charles I, Vol 1 (London, 1849), p. 226.