Tracing ‘Strand’ Across Land, Language and Time

Posted in Medieval, Strandlines, streets and roads and tagged with chancery, etymology, Maughan Library, old english, Savoy, strand

Today, the name of London’s most recognizable street, the Strand, evokes images of Trafalgar Square’s lions, the iconic Somerset and Bush houses, and, most of all, busied sidewalks alive with Londoners.

Those images, while impressive to locals and tourists alike, are tied rather arbitrarily to their street’s name. What brought the name to the place? Why ‘Strand?’

In contemporary use, ‘strand’ might mean to leave someone without help, as in ‘stranding’ a friend. When you hear the word, perhaps you might imagine a cotton fiber, as in a ‘strand’ of a string. The Strand in London, however, derives its name from a somewhat lost meaning of the word: ‘the land bordering a body of water.’

Most uses today of ‘strand’ that refer to its original meaning are literary or dialectic. However, the term in this context was once as common in English today as ‘beach’ or ‘shore’—the words that have arguably replaced ‘strand’ in everyday use. With this in mind, the connection between the iconic London street bordering the Thames and its name becomes clear.

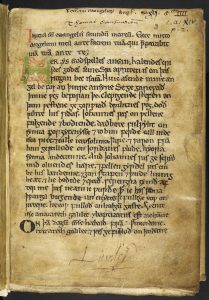

Some of the first documented uses of the word ‘strand’ in its land-bordering context were written around the year 1000. The word’s first recorded use is in biblical context, appearing in multiple books of the West Saxon Gospels—also known as the Wessex Gospels—the ‘translation of the four gospels [of the Christian Bible] into the West Saxon dialect of Old English.’[1]

Opening page of Marks Gospel, Wessex Gospels (London, British Library, MS Royal 1 A XIV, f. 3r).

In this Old English text, ‘strand’ may be one of the few instantly recognizable words for modern English speakers. The Gospel of Saint John in West Saxon (not pictured) reads, ‘…on ærne mergen se hælend stod on þam strande,’ roughly translating to ‘at early morning the savior stood on the strand.’

Notice the word’s ties to the West Saxon dialect of Old English, in particular. West Saxons, who inhabited south and southwest England, derived from a larger Germanic people in Old Saxonry.[2]

Before the emergence of ‘strand’ into the West Saxon dialect of Old English, the etymology of ‘strand’ shows it resided in Old Frisian as ‘strônd.’ The Saxons actually bordered the Frisians on the continent, explaining the term’s jump from Old Frisian to Old English when some Saxons migrated to England.

Movement of Germanic peoples to present-day Great Britain. From the British Library.

‘Strand’ derives from the same root as Middle Low German’s ‘strant’ and Old Norse’s ‘strǫnd .’ Today, the word still appears in its original meaning as names of beaches in Ireland and Scotland, like Portstewart Strand and Silver Strand, showing how ‘strand’ became embedded in Irish and Scottish culture. The word has crossed land and language in its journey over time.

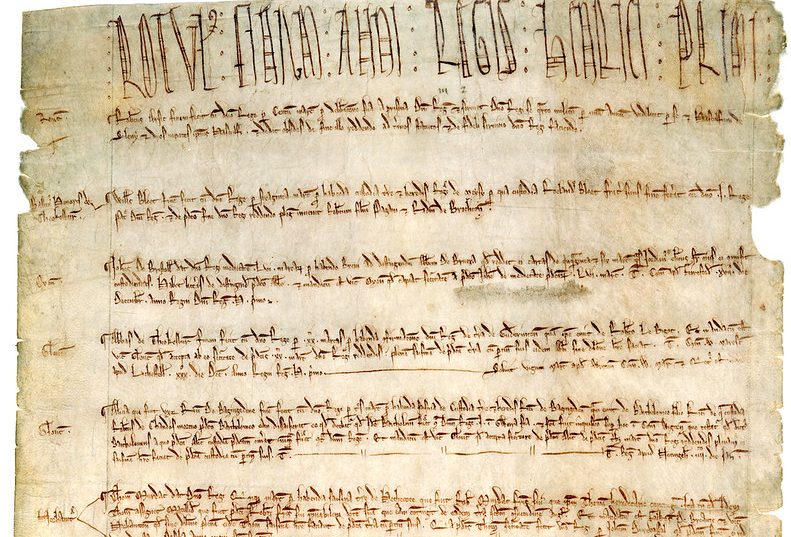

As for the first documented uses of the word ‘strand’ to refer to London’s most central street, the honor belongs to King Henry III. In 1246, the king issued a transferral of a property on the Strand to Peter of Savoy. The text, written in Latin, granted Savoy “domos..extra muros Ciuitatis nostre London, in vico qui vocatur le Straunde,”[3] translating in English to “houses… outside the walls of our city of London, in the street called the Strand.”

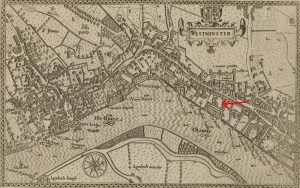

The Strand in 1593 (the Norden Map). British Library (Public Domain). The drawn-on arrow shows the approximate location of land transferred to Peter of Savoy by King Henry III, which became the site for Savoy Palace while the palace existed. Edited image from the Queen Mary University of London History blog.

This document containing a transfer of land ownership was scribed on a chancery roll, similar to what we call public records today. Chancery rolls are ‘a series… which were begun in order to record offerings made to the king or his justiciar for royal favour,’ but ‘miscellaneous material sometimes appears on the dorse of the membranes,’[4] or back of the pages.

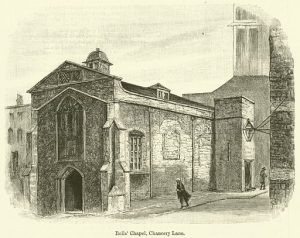

Like records offices today, whole buildings were dedicated to the care and keeping of chancery rolls. One former Rolls House may be familiar to Strand-goers today: the Maughan Library.[5] Perhaps Henry III’s documentation of the ‘Strand’ as a name once resided in the former Rolls House and current Maughan Library, which is housed (rather aptly) on Chancery Lane.

A sketch of the Rolls’ House and Rolls’ Chapel on Chancery Lane, the remains of which now form part of Weston Room in Maughan Library. From Look and Learn History Picture Archive.

It is likely safe to conjecture that the street we now call the Strand was being named as such informally before it was ever recorded formally in chancery rolls. All the same, extant documents, like chancery rolls, are our best resource for keeping track of uses of ‘strand’ and other historically significant words.

Around the same time that ‘strand’ was being used to denote the London street, the term was also being etched into significant works we still use as reference points for Middle English literature. Among others, ‘strand’ appears numerous times throughout Layamon’s Brut, also known as the Chronicle of Britain, and The Story of Genesis and Exodus.[6] These works help keep Middle English uses of ‘strand’ relevant to us today and remind us of the word’s roots in biblical texts and poetry.

While ‘strand’ is culturally relevant to us mostly through our access to the London street, uncovering its widespread use in the past helps us keep in touch with its history, and therefore London and England’s history. Perhaps the history of the word ‘strand’ invites us to view the bustle of London’s most well-known street with a renewed sense of beauty.

Further reading:

[1] “Written in Troublous Times:” The Wessex Gospels. (2013). Medieval Manuscripts Blog, British Library.

[2] “Who were the Anglo-Saxons,” Julian Harrison, British Library https://www.bl.uk/anglo-saxons/articles/who-were-the-anglo-saxons

[3] “strand, n.1d.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, November 2020.

[4] “Chancery: Fine Rolls.” The National Archives. Catalogue.

[5] Banerjee, Jacqueline. (2015). The Maughan Library, King’s College London (formerly the Public Record Office) by Sir James Pennethorne. The Victorian Web.

[6] “strand, n.1a.” OED Online.

[…] the shore of the Thames. For more details on this etymological evolution, I encourage you to read Tea Emily Carter’s piece! He mentions ‘reiterating’ the Strand. By this he means to walk up and down the shore, […]