Tourists on the Strand in the 1860s: A whirlwind tour from New York to the Temple Bar

Posted in 1800-1899, 19th Century, entertainment, people, Strandlines, streets and roads, Transport and tagged with Aldwych, History of London, history of tourism, London, London history, London tourism, New York, strand, Temple Bar, visit Britain, Visit London, Westminster

Introduction:

On July 1st 1867, American journalists published their reports of traveling through London back in the United States. A Brooklyn-based newspaper called the Circular (1851-1870) was printing the series named, “Journal of European Travel.” Where we can view London, as if a tourist, from over 150 years ago! What might surprise you is how little things appear to have changed within the city.

Why were the Americans in London?

It might seem odd to some readers that Americans would be visiting as tourists in the mid-nineteenth century. The Americans had recently finished a four-year civil war (1861-65) and were in the early phases of Reconstruction. Therefore, this expedition to London might seem surprising. I can assure you that it is not as strange as you might imagine.

Firstly, by the 1860s the movement of people across the Atlantic ocean had sped up quite dramatically. Around the 1850s, shipping companies had begun to use steamships to move people across the ocean. 1 This had cut the travel time to around two weeks. In London and Its Environs: Handbook for Travellers (1889), it is claimed

“The average duration of the passage across the Atlantic is 7 to 10 days. The best time for crossing is the summer.” 2

Secondly, the idea of travel-writing for the entertainment of others is not a new concept. People are always curious about places they’ve never been to or always wanted to visit. These American journalists chronicle their arrival in Liverpool, 24 hours after a stop in Queenstown (modern-day Cobh) and almost follow the London Handbook for travelers to perfection! They set off from New York, stopped in Queenstown, landed in Liverpool and took the train to London. 3

What did the Americans do in London?

So, the question now burning in your mind must be: what did they actually do in London? Well, the truth is not unlike an answer you could expect from a modern-day tourist.

“We arrived in London about six o’clock, and after tea started out for an hour’s walk in the city. Our hotel is almost within a stone’s throw of St Paul’s; and its great, magnificent dome was the first object which met our eyes. There it stood, head and shoulders above all the rest of London.” 4

Their admiration for St Paul’s certainly is a relatable point of view for any tourist in London, though being in a hotel so close seems less likely these days. St Paul’s Cathedral is a magnificent building and it would have been even more so in the 19th century, as it was the tallest building in London until 1963. Notice the scale of the cathedral relative to the city skyline.

This gives us a good starting point for their adventures.

What about the Strand?

“We tore ourselves away from St Paul’s reluctantly, and walked down Fleet-st, through Temple Bar, down the Strand to Charing Cross, and back to our hotel, through Holborn. These names had long been familiar to me in a dim, far-off way, and I enjoyed very thoroughly the making them a part of my every-day life. Temple Bar! can our people imagine how it makes one feel to go under that time-stained arch, which Shakepseare, Lord Bacon, Cromwell, old Henry the Eighth and his five wives, had all doubtless traversed before me?” 5

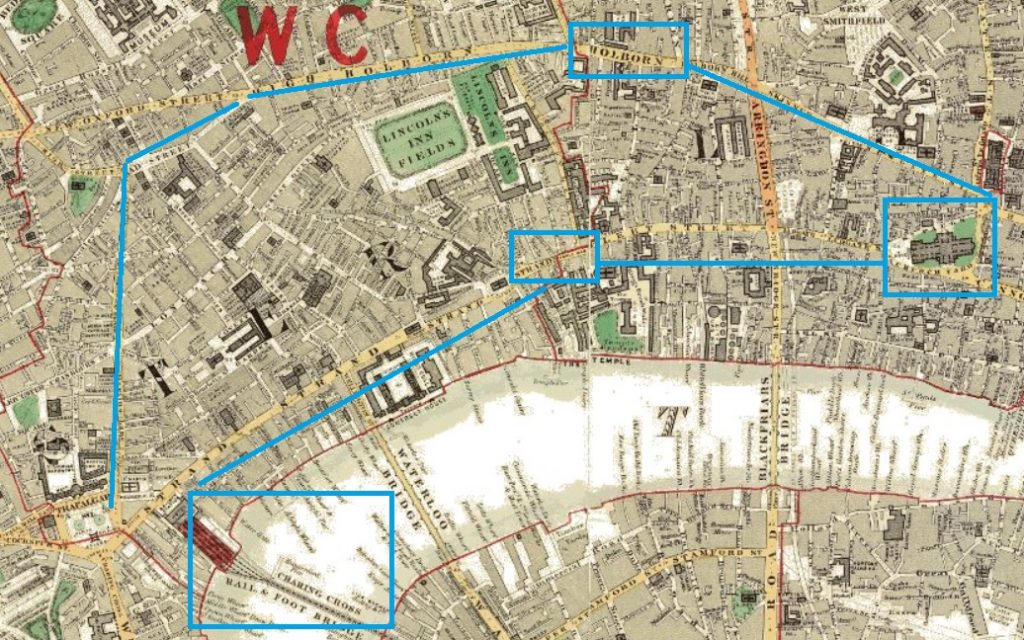

Path of the American tourists in 1867 roughly marked on an 1862 map of London.

The American tourists took a whirlwind tour of central London in their first day. The above passage offers many details concerning their trip. Firstly, the path of the 19th century tourist and the modern tourist does not differ as much as you might think. Secondly, the idea that London’s best known locations are known by name to many people, whether they have been there or not is a continuing thread from past to our present. Thirdly, what was ‘British-ness’ from the perspective of an American 150 years ago? The author’s choice of known figures is a telling indicator of how London was perceived by Americans.

Lastly, keeping with this theme, the Temple Bar is chosen as the central location to epitomise London as an ‘eternal’ or ‘ageless’ city. The Americans are in awe thinking at how many generations of peoples have walked under this gate to enter the City of London. This is not surprising considering how young the American republic was in this period, and how shaken it had been by the recent civil war.

A more detailed look at their walk:

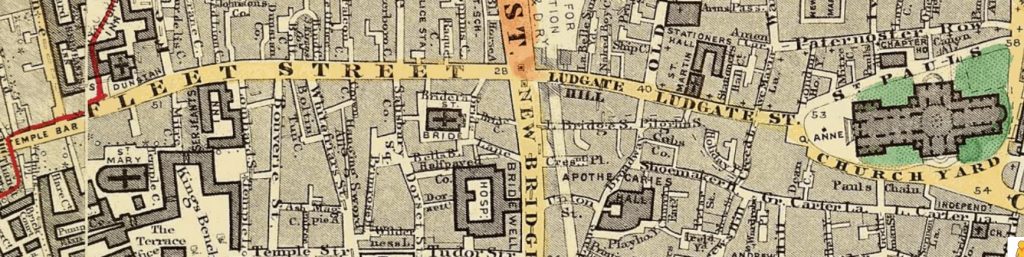

First leg of the walk: St Paul’s to the Temple Bar.

Second leg of the walk: Temple bar to Charing Cross.

You will notice many key elements of the Strand on these close-ups of the map. Temple bar, St Clement Danes, Somerset House, the Savoy Wharf (just south of the soon-to-be built 1886 Savoy Hotel), and finishing up by Charing Cross.

London: international or British?

“If no man can know London, neither can any nation claim London. It disdains the audacity of special ownership that is may give itself to mankind. It is for this reason, no doubt, that the foreigner in Great Britain often experiences a relief in passing from even the larger provincial towns of the kingdom up to the metropolis. In Liverpool and Manchester he feels that he is on Englishmen’s ground, in Glasgow and Edinburgh on Scotchmen’s, but in London on his own.” 6

In short, they notice that London is more an international city than it is a British city. As a French person who grew up a Londoner, I believe that does hold true to this day. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Which, coincidentally, is a French saying coined by Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”.

Is London too big?

The Americans published two articles in the Circular on their London adventures, the first (from July 1st 1867) heavily focuses on their time in London. Their second, from July 22nd, focuses on the state of London at that time. One concern brought up repeatedly, which continues to have relevance to this day, is the burgeoning size of London. Observe this snippet from the July 22nd article:

“In the present magnitude of London it is amusing to remember the comments upon its greatness made by Addison or Burke or Dr Johnson at a time when it was to its present self what the babe is to the man. One Good Friday, Johnson and his man Bozzy trudged together along the Strand to attend service at St Clement Danes. Bozzy remarked “London was too large” […] It was then about one-sixth its present size.” 7

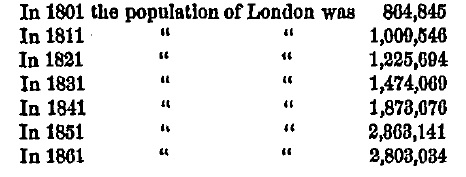

They also presented the following data to their American readers:

London population size from 1801 to 1861.

A certain Mr Benjamin Scott (chamberlain of the city) calculated that at the current pace of development, the population of London would be over 8 million people by 1911. 8 Luckily the population growth did not prove to be so radical although, it is very intriguing that the Americans dedicated almost the entirety of their second article to this theme. People feared overpopulation even though London was built with such rapid expansion in mind. The mere existence of the Temple Bar in the 1860s, to split one of the main viaducts of London in two, shows the poor city planning.

Overcrowding concerns continue to this day.

Clearly, the New Yorkers were impressed. This is not entirely surprising as the New York government now estimates the population of New York city to be around 813,000 people in 1860. 9 Please note that the NYC municipal borders expanded to their current geographical locations in 1898, which would have affected the numbers.

Concluding thoughts:

Looking at London through the eyes of American journalists from over a century and a half ago turned out to be quite a winding road from their trip over to London, to their walk around central, and finishing off with thoughts on the demographic growth of the area. These writers have left a looking glass for us to peek at a London that is now long-gone. It is clear that London has both changed tremendously and remained constant. This is best symbolised by the Temple Bar. It was moved due to congestion in 1878, to allow growth for the city. Yet, it was reassembled next to St Paul’s to be eternalised. 10

Further Reading

- John Simkin, “Journey to America.” Spartacus Educational (1997).

- Karl Baedeker, “London and its environs: Handbook for Travellers” (1889)

- C, S. J. 1867. “Journal of European Travel.: II.” Circular (1851-1870), Jul 01, 125.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “London.” Circular (1851-1870), Jul 22, 1867.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- New York City Department of City Planning, “1790-2000 NYC Historical and Foreign Born Population” (2004)

- City of London, “Temple Bar – Our buildings in the City” (2012)

Another pleasant read. I will have to visit this ‘Temple Bar’ when I get a chance to visit London so that I may be transported back in time and view a part of the city as if I were one of these mid-nineteenth-century American journalists myself. I will buy a round for the author, bravo.