Building Bush House: Britain and America’s ‘Special Relationship’

Posted in 1910-1919, 1920-1929, 1930-1939, 1940-1949, 20th Century, Architecture, Strandlines, wartime and tagged with building, Bush House, design, London history, Savoy, strand architecture, World War I, World War II

Before Bush House was home to the BBC or, more recently, to King’s students, it was a personal project of one Irving T. Bush within his larger agenda of cementing America and Britain as pillars of international trade.

Bush’s vision for an international trade centre was unlike the primarily electronic centres of exchange we might imagine today. His initial plans for the building included plenty of space for exhibition galleries, where manufacturers could lease out the floor to show off their products to buyers, but also incorporated a number of luxury features that may feel extraneous to the financial trading world. Amidst the neo-classical detailing, Bush House housed an indoor badminton court, a swimming pool, a cinema, reference libraries, and even its own artesian wells by the time it was completed.1 A 1925 brochure promoting Bush House boasted of ‘tea, towel and duster services’, ‘courteous and efficient house staff’, and ‘high-class lavatories’.2 The building’s construction began in 1923, and although further additions were made up to 1935, Bush House officially opened on 4 July 1925—United States Independence Day.3

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbzXg2q-uVo

In step with Bush’s hopes for a strong ‘Anglo-American’ partnership, the opening ceremony involved the unveiling of the building’s most recognizable architectural feature: two male statues representing Britain and America jointly raising a torch, standing in a 100-foot-tall archway overlooking Kingsway. The instalments’ inscription, legible from the street level, dedicates the space ‘to the friendship of English-speaking peoples’.

Statues Britain and America raising a torch, with inscription ‘To the friendship of English-speaking peoples’ below them. From John’s World View blog.

This inscription, and Bush’s goals, were part of a larger impulse toward ‘Anglo-Saxonism’ in Britain and the U.S. in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. ‘Anglo-Saxonism’ was (and is) a belief in the primacy and supremacy of English-speaking nations.4 Several organisations, comprised mostly of London and New York’s elite, cropped up with the explicit purpose of fostering a close relationship between Britain and the United States, mostly through displays of public diplomacy. These organisations—the most influential perhaps being the Anglo-American League, the Atlantic Union, and the Pilgrims Society—facilitated conversations between statespeople and their own members by acting as transcontinental social clubs: banquets and dinner parties set the stage for London and New York’s wealthy to become unofficial actors in public diplomacy.5 The Strand was an official setting for such conversations not at Bush House, but at the Savoy Hotel, where the Pilgrims Society kept offices and hosted banquets.

Although Irving T. Bush was not an official member of these organisations, his intentions aligned with theirs. In his autobiography, Bush points to the similarities between Britain and the U.S. as an indication that the two should not only learn from one another, but that they should position themselves to profit economically from the rest of the world. He endorses ‘complete unity… among all of the English-speaking branches of the British empire’ and emphasises its ability to prop up the English economy. Ultimately, Bush interests himself in Britain because ‘a glimpse of the difficulties surrounding England’s future… may safeguard [America’s] own’.6 According to the promotional brochure referenced above, in the short time Bush House operated as office space for international commerce as intended, it housed many American companies, perhaps further proof of Bush’s plans to build links between American and British business.

The building’s less conspicuous exterior details, apart from its front-facing statues, also speak to Bush’s aims. On the rear of the building, stone carvings depict a ship crossing the waters between America and the U.K., with several prominent names from both U.S. and U.K. history framing the ship on either side.

Close up of stone carvings on Bush House rear facade. Original photography by Tristan Tetteroo.

Bush House rear facade. Original photography by Tristan Tetteroo.

The American names etched into the rear facade of Bush House, on the left of the ship: Washington, Lincoln, Grant, Hamilton, and Franklin. From John’s World View blog.

The British names on the rear facade of Bush House, to the right of the ship: Chatham, Burke, Canning, Bright, and Bryce. From John’s World View blog.

Bush House is not the benefactor’s only namesake. Across the Atlantic, Bush Tower rises 30 stories into the Manhattan skyline, built for the same purposes as its London counterpart—to secure places of leadership in international trade for America and Britain. Bush hired the same American architect to design and build both: Harvey Wiley Corbett. Bush House was not, then, subject to the same architectural processes other notable buildings on the Strand were, such as the lengthy and dramatic competition that decided the architect for the Royal Courts of Justice. Bush and Corbett, instead, working together relatively often, developed a relationship that allowed Corbett to spend freely on architectural details that Bush financed.7 It is no surprise, then, that Bush House was once declared ‘the most expensive building in the world’, its construction costs topping an estimated two million pounds.

The building’s exterior was likely no small contribution to its list of expenses, being built of Portland stone. Bush House’s stone exterior links it not only to other London landmarks constructed with the same material, like St. Paul’s Cathedral and Buckingham Palace, but to a building of consequence back across the Atlantic, too: the United Nations building in New York.8 Although Portland stone is incorporated in a diverse set of structures, the symbolism of this pairing particularly is reflective of the goals of public diplomatic efforts by U.S. and U.K. elites at the time. While New York and London’s wealthy and powerful made efforts to cement a ‘special relationship’ between the U.S. and Britain, the built environment seemed to reflect the growing bond between the two. Bush House, meant to be a beacon for international trade, was constructed of the same materials as a building standing for global government, further setting in stone (literally) the influence America and Britain held politically and economically in the world.

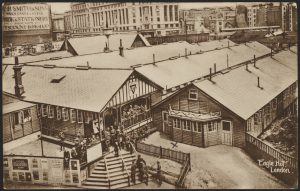

At the foreground of this growing relationship between America and Britain, and in the backdrop of Bush House’s construction, are two World Wars, each of which escalated official ties between the U.S. and Britain. Even before Bush planned his London trade centre, the land Bush House sits upon was wrapped up in American and British relations. The site was home to the ‘Eagle Hut’ during the First World War, established by four American businessmen and run by the Young Men Christian’s Association (YMCA). The Eagle Hut provided a place for British and American servicemen to eat, drink, and fraternise while they were stationed in London.9 Today, the Eagle Hut is commemorated by a plaque on Bush House which contends, notably, that the Eagle Hut’s services ‘testified to the friendship of the English speaking peoples’, the same inscription that marks Bush House’s South Wing statues.

Inscription on Bush House commemorating the ‘Eagle Hut’. From London Remembers blog.

The Eagle Hut, built partially on the future site for Bush House. From Springfield College, Creative Commons.

Those statues, which had been erected by the time the Second World War broke out, felt an effect of the violence. A bombing raid hit the front of Bush House and the statue representing America lost its left arm, again an interesting moment of symbolism. Although the America statue lost an important limb, one which might symbolise a loss of strength, its right arm remained connected to the stone torch, and therefore to the statue representing Britain. It is almost as if the damage to America’s left arm only further accentuated the importance of a relationship between Britain and America for the sake of their combined power. For several decades after the war, the statue remained deformed; it was not until 1977 that an American company restored America’s left arm.10

Closer image of Bush House statues Britain and America. From JRA.co.uk.

Before the Second World War, Bush’s hopes for his trade centres to become beacons of U.S. and British financial power had already been dashed. The unique concepts he incorporated into both Bush House and Bush Tower did not receive the level of interest by manufacturers necessary for the buildings to be used as such, and by 1923, when Bush House was completed, a financial slump in trade and manufacturing sealed the fate of Bush’s ambitions.11 Bush House was adapted for more traditional office use, and soon Bush House’s longest tenant, the BBC, moved in.

Many of the unique features Bush and Corbett incorporated into the original design of Bush House have since been removed, as various refurbishments aimed to make the space utilisable for office and university work. Bush House may never have lived up to its namesake’s hopes, but the history of its construction and the land it is built upon will always be a part of the establishment of the ‘special relationship’ between the United States and Britain.

Further reading:

O’Brien, Kate. “Bush House: Early Construction mid-1920s”, YouTube, produced by Jessica Borge/KCL Archives, 2021. https://youtu.be/tbzXg2q-uVo [Accessed 9/7/2021]

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160228200005/http://www.kcl.ac.uk/aboutkings/orgstructure/ps/estates/Real-Estate-Development/current/aldwych-quarter/bush-house-history.aspx

- See YouTube video below for a look through the full look through the brochure, relevant press clippings, and blueprints from 1930’s construction.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120629173014/http://www.bbc.co.uk/historyofthebbc/collections/buildings/bush_house.shtml

- For a recent scholarly examination of Anglo-Saxonism, see: Karkov, Catherine. Imagining Anglo-Saxon England: Utopia, Heterotopia, Dystopia. Boydell & Brewer. 2020.

- Bowman, Stephen. The Pilgrims Society and Public Diplomacy, 1895-1945. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Bush, Irving T. Working with the World. Doubleday. 1929. pp. 234-236.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-18786495

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portland_stone

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160228200005/http://www.kcl.ac.uk/aboutkings/orgstructure/ps/estates/Real-Estate-Development/current/aldwych-quarter/bush-house-history.aspx

- https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/buildings/bush-house

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/us/010119_bushhouse.shtml