Savoy to Albemarle: The Tale of Wilde’s Demise

Posted in 1800-1899, 19th Century, Editorial blog posts, Education, hotels, Literature, Memory, people, Places, restaurants, Stories, Strandlines, Strands and tagged with 19th Century, Albemarle Club, central London, History, Literary London, Literature, London, London history, London in literature, Mayfair, MyStrand, Oscar Wilde, Piccadilly, Savoy Hotel, strand, Strandlines, Victorian, Victorian Literature, writing

The Savoy

On the 2nd March 1893, the Savoy Hotel’s adjoining rooms 362 and 361 were checked into by an Oscar Wilde rapidly approaching the apogee of his dramatic career. Soon to be joined by Lord Alfred Douglas – or ‘Bosie’ – to whom Wilde had been introduced some two years earlier, the pair would go on to stay at the Savoy for the entirety of March. During their stay, Wilde and Bosie racked up a staggering £63 and seven-shilling bill on food and drink consumption alone, equalling around £3,800 today. At a bankruptcy hearing years later, Wilde would reveal he spent £5,000-£8,000 per week on their antics in London, regularly keeping tabs they’d never pick up. Wilde had, in the wake of Lady Windermere’s Fan’s success the year prior, become ‘a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion’, and, as he later reflected from prison, was ‘lured into the imperfect world of coarse, uncompleted passion, of appetite without distinction, desire without limit, and formless greed’.

The period of March 1893 to February 1895 would see Wilde estrange his wife, Constance, and two children, Cyril and Vyvyan, in pursuit of sating this ‘appetite’. Indeed, journalist Neil McKenna reflected in 2004 that during this first month of March at the Savoy – which would ultimately prove fatal – ‘food and sex became inextricably intertwined’, as Wilde and Bosie sought to gorge on both cuisine and an array of young men. Much of what happened at the Savoy comes from the testimony of Jane Cotta, a chambermaid who described the state of Wilde’s stained and soiled sheets, as well as circulating rumours amongst the pageboys of Wilde’s notorious kisses and half-crown tips. Oscar likened the month to ‘feasting with panthers’ – ‘the danger was half the excitement’.

The rooms at the Savoy had been taken up on Bosie’s request (better described as demand) following a heated row the two shared down at Babbacombe Cliff, Torquay, while staying in the empty mansion of one Lady Mount-Temple, Constance’s close friend and confidante. Oscar and Constance had been there since November 1892 with the children; Oscar then fled to London for a period of ‘respite’ in January, only to return to take care of Cyril once Constance had to travel to Florence. Oscar then back in Babbacombe, Bosie spontaneously elected to drive down to stay with him, dragging his baffled Oxford private classics tutor along for the journey. What exactly Oscar got up to while back in London, and the nature of the conversations shared between Oscar, Bosie and his tutor, Campbell Dodgson – in what Oscar dubbed ‘the Babbacombe school’ – each served as omens for what lay ahead.

The Savoy interior, July 2021

First, London: in Autumn 1892, a few months before the Babbacombe trip, Wilde had been introduced to Alfred Taylor, an Old Marlburian with more inheritance than sense, who’d taken rooms on Little College Street just behind Westminster Abbey, and had a predilection for young, attractive male company. Taylor would admit during his deposition to acquainting Oscar with a host of young men, five of whom would testify against him: brothers Charlie and William Parker, ‘Jenny’ Mavor, Fred Atkins, and Alfred Wood. Many of the boys Taylor picked up were homeless ‘renters’ (semi-professional blackmailers and sex workers), and many of them were forced into giving testimony, threatened with prosecution themselves for pettier crimes. During Oscar’s ‘respite’ from domestic life in the south-west, it was Alfred Wood he had travelled back to London to see. The pair would sleep together at Oscar’s family home on Tite Street on and off for a week in January before Oscar’s return. As with many of Taylor’s rent boys Oscar would whisk off to the Savoy or Albemarle Hotels, he afterwards presented Wood with an engraved silver cigarette case – homoerotic symbolism abounding.

Second, the Babbacombe School: Bosie had recently failed an exam at Oxford and required the assistance of Campbell Dodgson to catch up. At Mount-Temple’s mansion, while Cyril studied French in the nursery, Oscar would take intermittent breaks from drafting The Importance of Being Earnest to come downstairs and argue with Bosie and Dodgson ‘for hours in favour of different interpretations of Platonism’. The reference to ‘Platonism’ is especially important. Depending on who you ask (much argument to the contrary seems to be derived from Frank Harris’ belated claims of an admission Oscar made to him years later, which, for example, biographer Hesketh Pearson rejected outright in 1946, but which Neil McKenna in 2004 accepts wholesale), sexual attraction was very much secondary in the allure of young men for Wilde. During the first of the crown’s later two trials, while being cross-examined by prosecutor Charles Gill regarding a poem Bosie had written, ‘Two Loves’, Wilde was asked to define the ‘Love that dare not speak its name’, to which he obliged with the following speech, receiving a standing ovation:

The ‘Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is so pure and so perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art […] It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the ‘Love that dare not speak its name’, and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.

The ‘Platonism’ Oscar was describing was pederasty, to which he unabashedly admitted. While some of Taylor’s boys undoubtedly engaged in sexual relations with Wilde to varying degrees, there are several accounts – particularly from those boys Oscar entertained at the Savoy – of purely intellectual encounters, during which Oscar would effuse about the wonders of youth and art, across from a (presumably dumfounded) young man, for whom he would leave £2 the following morning.

Oscar and Bosie ultimately fell out over some triviality at Babbacombe and, after a brief check-in with his mother in Salisbury, Bosie would follow after Oscar to their pre-booked rooms at the Savoy. The events of their ‘grossly materialistic’ stay, and the ensuing two years of clumsy hedonism, would soon be unearthed by Bosie’s own father, the Marquis of Queensbury.

The Albemarle Club entrance, July 2021

The Albemarle

Hesketh Pearson’s opening account of Lord Queensbury reads: ‘[he] was, we may charitably assume, a madman.’ I would amend this slightly, and say that The Marquis of Queensbury was a raging homophobe; that is to say, he exhibited a constant and unfaltering display of rage, and the single most prominent hallmark of a homophobe: fear. His eldest son and Bosie’s older brother, Lord Drumlanrig, had engaged in an illicit Uranian affair with the soon-to-be prime minister Lord Rosebery, before committing suicide in late 1894. Queensbury blamed Drumlanrig’s ‘unnatural disposition’ for his death, and assumed the ‘heroic’ position of forbidding homosexuality to dirty another of his sons.

Earlier in 1894, during the midst of Wilde and Bosie’s escapades (now inhabiting not the Savoy, but Oscar’s rooms on St James’ Street), Queensbury bumped into the pair at the Café Royal in Piccadilly. Bosie invited him to dine with them both and Queensbury, apprehensive, acquiesced. Within ten minutes, Wilde had Queensbury completely enchanted, openly laughing and basking in Oscar’s quick wit. Later that night, he wrote to Bosie: ‘I don’t wonder you are so fond of him; he is a wonderful man.’ But mere days later, while standing near a window in Carter’s Hotel, Queensbury spotted Wilde and Bosie rock up in a hansom cab just outside the Albemarle Club, and watched Wilde ‘caress’ Bosie in ‘an effeminate and indecent fashion’. He immediately saw red. A number of insidious letters were written to Bosie imploring he cease communication with Wilde, threatening to publicly ‘thrash’ him should he not comply. Bosie, naturally, chose to poke the fire, replying in turn with a single telegram reading ‘what a funny little man you are’. Queensbury continued to threaten violence should he see Wilde and Bosie dining together, and Bosie continued to reply with the exact details of their dinner reservations.

On Valentine’s Day 1895, Queensbury conspired to sabotage the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest by throwing a basket of rotting phallic vegetables at Wilde as he delivered his usual post-performance address, publicly exposing and shaming him for being a sodomite. Unsurprisingly, Queensbury was less than discreet about his plans, and Wilde caught wind of them beforehand. Queensbury’s ticket for the performance was cancelled and refunded, and upon his turning up anyway, police were stationed at every entrance. Enraged, Queensbury hatched another plan. Some time between the 18th-22nd February at 4:30pm, Queensbury turned up to the Albemarle Club – a progressive club at which Wilde was a known member – and demanded to see Oscar himself. Upon being informed by Sydney Wright, the young hall porter, that Oscar was away (on a two-week gallivant reacquainting himself with the Victorian aristocracy), the fuming Queensbury produced a printed visitors card and scrawled on the back: ‘To Oscar Wilde ponce and somdomite’. (His messy hand and shoddy spelling later proved advantageous, as he amended the note to read ‘To Oscar Wilde posing as sodomite’, for which a conviction would be easier sought.) He handed the note to Sydney, saying only, ‘give that to Oscar Wilde,’ and left.

Wilde arrived back at the Albemarle on the 28th February, at around 5:00pm. Sidney had kept the note stowed in an envelope and handed it to Wilde: ‘Lord Queensberry desired me, sir, to hand this card to you when you came into the club.’ Oscar took a moment to decipher the note and recognise its author, before flouncing off to the Avondale Hotel, Piccadilly, to rendezvous with his long-time friend and ex-lover Robbie Ross and, of course, Bosie. Their immediate decision was to sue Queensbury for libel, though Queensbury’s obvious defence would be to attempt to prove the libel in fact truthful, rendering his actions a public good. Queensbury’s solicitor Charles Russel recruited former Scotland Yard Detective-Inspector John Littlechild and retired Detective-Inspector Frederick Kearley, who, along with Charles Brookfield – an actor then starring as Lord Goring’s servant in An Ideal Husband and outspoken homophobe – supposedly ‘raked Piccadilly to find witnesses against Oscar Wilde’.

Sex workers, pageboys and renters were harassed by Littlechild, Kearley and Brookfield, presenting those who knew Wilde the ultimatum of testifying against him or facing prosecution themselves, and enticing those who didn’t to fabricate stories incriminating him. At this point, the libel suit was losing strength and the risk was beginning to far outweigh the reward. Wilde’s decision to persevere with the suit in face of the impending danger has since, Pearson posits, ‘troubled many’, and as to why, ‘no satisfying answer has yet been given’. McKenna’s exegesis is a Wilde inebriated and weak-willed, swayed by a Bosie desperate to see his father ‘in the docks’, while Pearson’s Wilde privately romanticised himself as a figure of the Fall: seduced by biblical imagery and a particular palmist reading he’d received years prior foretelling his own doom, Wilde saw the loss in court as the necessary impetus to set into motion a misfortune already predestined. In a letter to Robbie from the Avondale, he wrote:

My whole life seems ruined by this man. The tower of ivory is assailed by the foul thing. On the sand is my life spilt.

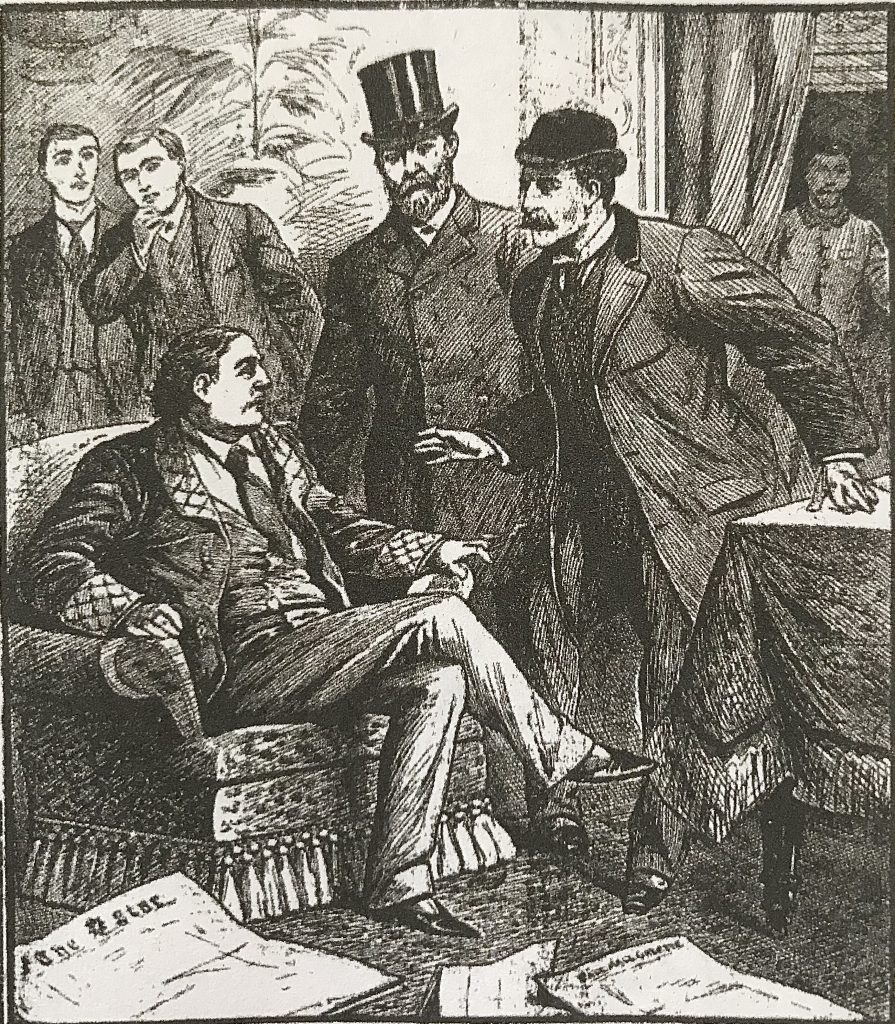

Wilde’s arrest at the Cardogan Hotel, Sloane Street, 1895

The Stand

Once Oscar’s libel suit had inevitably proved fruitless and Queensbury was released, Oscar himself was detained just days later on April 6th 1895, for the first of what would turn into two discrete prosecutions by the crown. Alfred Taylor was brought to court alongside Wilde, and the crown initially tried to convict the pair with ‘conspiracy to commit indecent acts’; Taylor’s landlady at his Chapel Street house, Sophia Gray, to whom he still owed money, readily handed over a hatbox full of documents to the prosecution which contained a ‘veritable goldmine of information’ regarding Taylor’s rent boys and clientele. The conspiracy charge fell through with a split jury (not least due to Wilde’s charm on the stand), and a second trial was instigated by none other than the Solicitor General, Sir Frank Lockwood, just a fortnight later. Everybody involved seemed desperate to convict Oscar – Lockwood himself to protect his own son, Maurice Schwabe, who had introduced Wilde to Taylor and slept with Wilde on multiple occasions – not least of whom being Oscar, who, with the opportunity to flee abroad, opted once again to stay, somehow convinced that he was meant to suffer this defeat.

Bosie was notably, in the mutual interest of Wilde and Queensbury, omitted from the trials. Alfred Wood, Fred Atkins and a handful of Taylor’s other boys Oscar had received at the Savoy and Albemarle Hotels were called to the stand, ‘cajoled and terrorised’ by Queensbury’s solicitors into giving statements. William Parker testified to going to dinner with Taylor and Wilde and his brother, Charlie, at Kettner’s, during the course of which Oscar fed Charlie from his own fork and seductively placed cherries into his mouth; Charlie testified to being taken back to Oscar’s rooms at the Savoy and being asked to perform oral sex, before being sodomised. Sidney ‘Jenny’ Mavor testified to having sex with Oscar at the Albemarle Hotel in September 1892, after which he received a small silver cigarette case delivered to his house in South Kensington. Fred Atkins accompanied Oscar to Paris ostensibly as his ‘secretary’ in early November 1892, during which and for some time afterward they continued to sleep together.

Taylor and Wilde were deliberately tried sequentially the second time round on May 22nd – Taylor first – so that, even in failing to charge with conspiracy, the ease with which Taylor would be convicted would convince a jury of Wilde’s guilt by association. Upon hearing the witness testimony and securing a guilty verdict, presiding judge Justice Wills declared the whole affair ‘the worst case I have ever tried’, and sentenced the severest term the law would allow of two years’ hard labour: ‘in my judgement it is totally inadequate for such a case as this.’ While initially shocked, gasping the dock’s handrail to steady himself, this was the fate to which Wilde had resigned himself. In a letter to Henry Labouchère weeks later, Bosie would reflect on Oscar’s martyrdom:

Mr Oscar Wilde is fulfilling another martyrdom for nature’s step-children which if it bears fruit as I think it will, in an outburst of educated feeling which has been smouldering in England for years against laws of senseless cruelty and barbarity will not have been in vain.

Maggi Hambling’s ‘A Conversation with Oscar Wilde’, Adelaide Street, July 2021

Oscar’s trial stands historic as ‘the first great battle of the modern age between Uranian love and an uncomprehending, persecuting world’. From the Savoy to the Café Royal and Albemarle Club, from the Strand to Piccadilly and Mayfair, lie shreds of this history. The subtle glimmer of Westminster’s backstreets was snuffed by the grey of Bow and Vine Street, and as Oscar was shipped off to Reading Gaol he wrote to Bosie, his ‘sweet rose, delicate flower, lily of lilies’: ‘I am going to see if I cannot make the bitter waters sweet by the intensity of the love I bear you.’