The Pathway of the Imaginary

Posted in contemporary, Literature, Maureen Duffy, Strandlines and tagged with

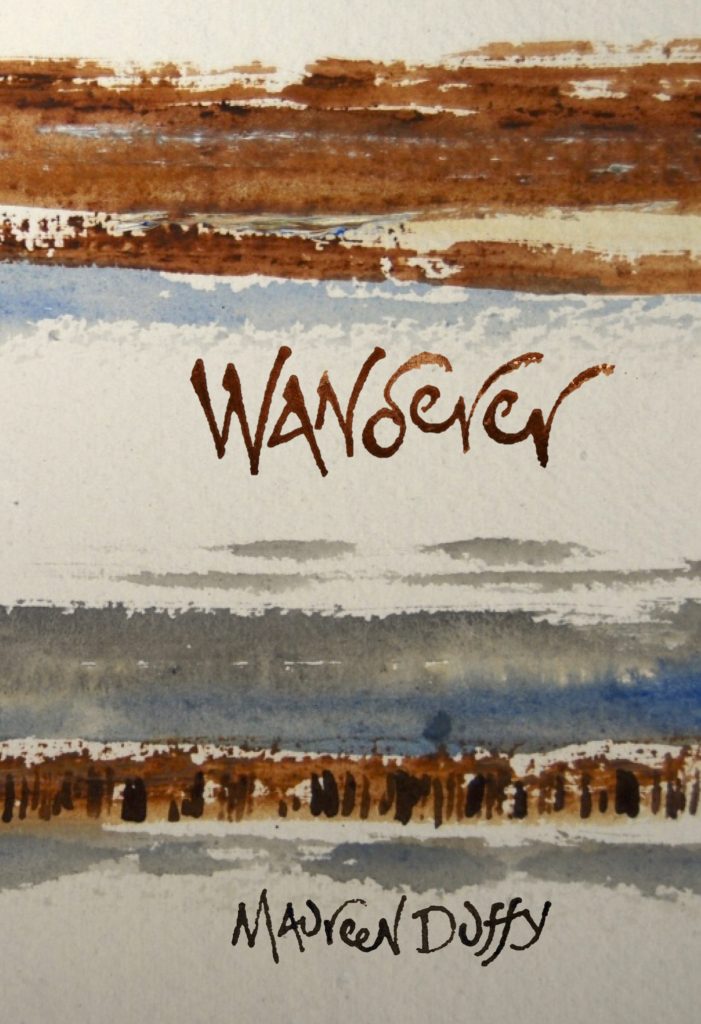

This article translation into English by Katie Webb from the original Italian, ‘Il sentiero dell’imaginario’ by Loris Ferri, was published in El Ghibli magazine on 10th December 2021 http://www.el-ghibli.org/il-sentiero-dellimmaginario/#sdfootnote2anc. El Ghibli is an international literary magazine for migration. The poem ‘Wanderer’ appears in the original English taken from the pamphlet Wanderer published by The Pottery Press in 2020 and with whose permission it is reproduced here. The Italian version published in the original article was translated into Italian by Anna Maria Robustelli.

Origins

It was in the summer of 2020 that I first met Katie Webb, who works with associations of authors all over the world through the international project IAF. Since then we have maintained a written correspondence and, seizing the occasion, we decided to meet halfway, in the Marche, Italy, in Porto San Giorgio to be precise. We talked of many things: of oral poetry, of my publications and Katie showed me a very interesting publication, a collection of poetry by the author Maureen Duffy called Wanderer, published by The Pottery Press 1 that year.

Forty eight pages corresponding to thirty one images (that set the poetry) by the artist Liz Mathews. The cover in particular struck me, that I felt like something bodily, tangible in the colours and there was more, an evanescence in the human figures, in the horizons, like a call, a call to enter, a want to disappear inside the image itself. From then on, the writer Duffy’s name has often come up in our conversations, and with the name the memory of those images. Katie had worked and was still working closely with the poet and after having supported the idea of translating some of my poems into English (mostly unpublished) I decided to accept her invitation to try to relate the homonymous poem ‘Wanderer’, which gives its title to Maureen Duffy’s collection, to the poem ‘Esodo’ (Exodus), the closing text of my book Cinema Sarajevo 2 ‘We / have become ghosts wandering a continent / faceless’. I knew that Maureen was not only talking of exile and migration. I knew she was also talking about us.

Before the skies darken

In the beginning it was the bard, the ancient poet singer of the Celtic people, the wanderer, the one who fixed infinity in time, who gave voice to the world, whose story was eternalised in the Old English poem, contained in the Exeter Book, whose title is Wanderer. The author herself, Maureen Duffy, tells us how the inspiration, the echo of that text vibrates in her composition, not only the choice to keep the homonymous title, but also in the breath, in the alchemy that links, beyond the times and tyrants, all the great poets. And in these, the illumination of the knowledge of how to read the signs of the world, the universal human condition.

Then: the meditation of a solitary exile, the poet minstrel, who wanders between cold seas and paths of exile after having lost his patron master, in search of an other-place to consider home, in the presence of fate (in Old English wyrd) totally inexorable. But fate does not only contain the force of the past that determines the future, but also the marked destiny that dominates the past, in a closed circle in which every act is predetermined and destiny itself is incontrovertible. Today: the terrible journey, the unexpected landing, the figure of the wanderer that takes form in the appearance of new refugees, exiles in the contemporary geography of migration. Death, escape, memory, faint hope scratched by daily events. The fatigue of single steps.

The central part of the text comprises the theme of the journey, but it does not only represent a physical viaticum of exile or of the continuous pilgrimage with its thousand difficulties, but an interior journey. The collective awareness that we are all migrants towards the unknown. Not even the bard of that time was immune, and the initial lines in Old English recite (lines 2-5):

…though afflicted in the heart

he had to travel the streets of the sea

move icy waters by hand, beat

the footsteps of exile – fate is inexorable.

Clearly expressing her atheist and humanist perspective, the author, in her observations linked to the text, pauses in the existential dimension of nomadism: man is nomad, not only in space but in time, a kind of inherent contingency in its being, and draws the conclusion that the experience of exiles would be traceable to the lost bard. “We are a migratory species”, she says. The wanderer, daughter of constriction and of necessity (food, war, loss of one’s land). In this broad framework of reflection Maureen Duffy sheds new light on the original theme, changing the setting, placing us in the scene of a collapse, the collapse of a civilisation. The writing takes place as live action, the sequences in free verse trigger the shipwreck, the attempted landing and the infinite and human tension of life:

Wanderer

After the houses were broken to rubble and dust

the streets where the children played bloody with death

from the skies, Palmyra sacked and ransacked

the arches, work of earlier men, toppled

and the museum, where once I had charge of jewels

in gold and silver, of rich carvings and many coloured

gemstones, shattered like the glass cases housing

antiquity, we fled from our land over the border

North and then the long walk until we came

to the shore in a little cove, scrambling over rocks

wading through pebble shifting shallows.

‘I will take you,’ the man said, ‘across the sea

for a price. Look you can see the island not far

over the waters, where you will be safe and free.’

So I paid him. The waves were cold, grey and rough

the boat small. ‘It is close by, just a little way

so I leave you now.’ But the waves grew higher

bitter rain and hail beat upon our heads.

We huddled in the boat but there were too many

of us. The waves came over the side. We feared

to sink. Water waited for us with its chilling

embrace. I tried to row with my hands while the women

bailed with theirs. A seabird flew over our heads

crying as we sank lower. Then suddenly

out of the murk a boat coming towards us.

We stood up waving our arms, cried out like the seabird

but our boat went down on one side as we rushed

to the other, begging to be saved. The chill waters

closed over me. But I strove upwards and there a hand

reaching down, holding me fast from sinking back

pulling me up until I lay on the hard deck, saved

as others sank from sight into the cold embrace

of the sea. On shore kind people came with blankets

to wrap our shivering bodies, filled our bellies with food

until the guards came with guns herding us into a cage.

A man cried out: ‘We are not animals, we are human.’

Then we were tagged, docketed like cattle for sale.

Many days we waited only wanting to go on

until at last they opened our cage, let us walk out

to take to the air and see the sea this time

below us. Only to travel the long road again

towards the future, carrying the children

with all we had in the world on our backs.

And so on northward, the air growing colder.

I had not thought exile would be so chill.

Countries closed barriers against us. We tore

them down with our hands, climbed over

however high they built, beat against them

until we came to a land where we thought

to find our future. But there was no respite.

Cold faces were turned towards us, blank eyes.

We were the lost of the world with only the

memory of a once happier time. We

have become ghosts wandering a continent

faceless, transient, passing through on and on

echoing the human condition, travelling

from birth to death yet still longing, believing

that between there must be life, vibrant

hopeful, that keeps us walking.

The principle of a mirage

If, in Maureen Duffy, the refugees show the face of the lost bard, in Exodus, in the journey of the men, women and children that cross the border of a cannibal Europe from the east, is comprised the epic of an entire migrant population. The figure of the singer-exile in this component is twofold and immediately evident: the wanderers, those who emerge from an inhuman crowd of barefoot souls, take the ancient semblance of the Greek poet Homer (line 7). In them it is not only the word and the story that hold the memory, but the bodies themselves, travelling, they become heretic metaphor of a living epos; the rhapsody that is woven into itself, like a long serpent, the lines of the poetry, sewn inexorably to the ancient cheekbones of refugee heroes (line 2) prefiguring the myth of Aeneas. Therefore the refugee hero that Virgil presents us in the Aeneid as the founding myth of Rome and of the language of the poets. Dante himself in his voyage chooses Virgil as a guide to traverse Hell and Purgatory, not only as an archetype of a prophecy (il puer, IV, eclogue of the Bucolics), but as a source of inspiration and teacher of style (Inferno I, ll. 82-87). It is not by chance that the reference to the Aeneid happens in the second verse of Exodus. If we retrace the writing of the First Book, Virgil immediately presents Aeneas with a very specific epithet:

I sing the arms of the hero of Troy

Lavinia is a fugitive from fate and comes to Italy…

Beyond the empire that Aeneas will found, beyond the dark journey that awaits him, albeit guided by Fate (fas) that does not always have positive connotations for the hero, he is destined to be and to remain a refugee, a fugitive constricted to abandon a city in flames, Troy, destroyed by a war, which he never wanted to leave, obliged to confront terrible pain and misfortune at sea. And in the gloomy moments anticipating escape, Aeneas loses his bride, Creusa, and searching for her everywhere rediscovers only her ghost whichencourages him to continue the journey: Lungo esilio ti aspetta, tanto mar da scolare (long exile awaits you, so much sea to sail) (book 2, l.780). For sure, Aeneas, whose fate is immediately sealed, if he could he would not move from his land (book IV, 340 sgg.):

If fate gave me to live according to my heart,

if I could in my own way heal the troubles,

in Troy, first of all the sweet relics of mine

I would have collected, the palace of Priamo would be standing,

Pulpit, twice brought to the ground, I would have done it again for the vanquished!3

Nevertheless every living being is at the mercy of absolute decrees; and then nothing else is left but real life, and nothing else remains but to confront the shipwrecks (Book III, 192 sgg.):

When the ships were out and now no

land appeared, sky everywhere, everywhere was sea,

leaden echo over my head the storm thickened,

bringing night and cold, and the wave shivered in the darkness.

Suddenly the winds upset the waters and the sea rises,

scattered over the vast abyss we wander:

overcast the day has clouds, the humid night has made

the sky disappear, tearing the clouds that haunt the lightning.

Thrown off course we sail the blind sea.4

In the reading of this brief passage, we are faced with the imposition of darkness, with the nomenclature of souls in storm, that have characterised man since he appeared, which find sublimation in the epic; and the story of the events goes to the extreme attempt of an overcoming, of a redemption, but the only possibility, suffocated by the laws of the fathers, corresponds to the same end of the fathers, to the metaphorical cessation of their existence. Unrecognisable territories and constantly changing borders, identity and barbed wire torn to absurdity. And in this total and absolute short circuit of the real, only the scale of art allows us to traverse the pain. While in the words the special statute “of unity in diversity” is fulfilled, in the heart of the poets the mixing occurs made of sounds, echoes and persecution. The song mixes in the blood and from warm blood and from the nerves back to the verse. History teaches us nothing; it is the memory, alive, it is the muse that sings in us and lets the cosmos vibrate, lets us feel the whole of existence on our skin, with its wonders, its contradictions, sufferances, torments, aspirations. It is her, the sunlight for a new world. Here, beyond the borders and maps, the song, the day of the bodies, the hope of the journey:

Exodus

Not a nation, more than a nation, a migrant

crowd with refugee heroes’ ancient cheekbones

moving as caravans of rags – mound

of hunger blackened tongues – it reaches the places

where small anthills, colonies of grasses and wheat,

settled the windy sign of a border;

slowly the new Homers emerge from an inhuman mob

of barefoot souls, with their blind eyes, buried in fear,

engraved in sickening water. Men devour the ground;

and to the ground they return. Love has a time. Its time is the end.

On the peaks, where the old goats dare not face

the hollows of cliffs, hoist themselves as fences, in the mess

of masses, rags of lousy bivouacs. The morning is cooking

like a loaf of bread. Every little seed relies on the wind

and to unknown cracks, before coming – with moist peel – to light;

it becomes ear between ears. The day of wide bodies is gone.

Around closed doors of disaffection, men are breeding

men mixing themselves, children of one first god.

Half-breeds sowing, along centuries of blood, their own flesh.

A world has no borders but eyes. In which is celebrated

the beginning of a mirage. The cosmos is born naked; descendants

are born, they’ll smell of turmeric and barley, darkness,

berber pupils deep black. They’ll be the footprints

on the hard stone, the flavour in the fields of may,

the wrinkles of grains set in the cracks of a pomegranate,

the soil dug from roots; their mestizo faces will be the new god.

This post will be placed in the special collection for Maureen Duffy’s works after a wander in the Strandlines homepage.

The insistence of the Real brings us to the frontiers of once familiar shores.