‘I’d Rather Be an American Girl at the Savoy Hotel…’ — sponsored content, early-20th Century style

Posted in 1800-1899, 19th Century, hotels, Strandlines, theatres and tagged with Advertising, Bloomsbury, Dickens, Embankment Gardens, Gilbert and Sulllivan, Henry VIII, newspapers, Richard D'Oyly Carte, Thackeray, the Savoy

Sponsored content might sound like a development of the internet age, but far from it. On television and in the print media, companies have been managing their brands, shaping their public images and enticing consumers this way for years. Often called advertorials, these pieces blurred the lines between advertising or entertainment and objective journalism. They were a means of publicizing a brand and hooking consumers through engaging, flattering content rather than an outright ad. This was the softest of soft sells.

The marketing of the Savoy Hotel in American newspapers provides an illuminating example of advertorials’ emergence in early 20th century marketing, revealing the Savoy’s use of literary forms to establish its reputation abroad and attract an American clientele. Owned by Richard D’Oyly Carte, who was inspired by the opulence of American hotels, the Savoy first opened in 1889. Carte used the profits from his productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operas to fund the endeavor and specifically set out to establish the Savoy as London’s first luxury hotel, specializing in American-style comforts.

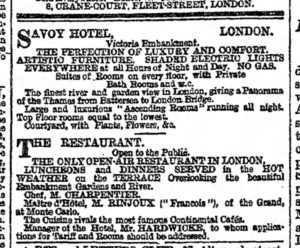

Figure 1: Advertisment in London’s Daily News, 17 September 1889

News of the new hotel trickled across the pond relatively slowly. In the U.S., the Savoy appears to have exclusively advertised with the New-York Tribune — then the paper with the highest circulation in New York City — from 1894 on.

Figure 2: Advertisement in the New-York Tribune, 28 October 1900

The Tribune appears to have been the Savoy’s primary marketing venue, with ads running in The Sun only periodically beginning in 1903. Over this same period, under new ownership, the New York Times had been working to increase its circulation from an abysmal 1896 figure of 9,000. The Savoy’s first advertisement with the Times surfaces in 1904. The ads in the Tribune had typically comprised about one column inch—twice the smallest ad size and consistent with those of the other international hotels, but still modest. Slowly, the sizes increased. During the holiday season of 1904, an elaborate half-column ad surfaced in the New York Times, which included blurbs from ‘the Press of England’ (plus, incongruously, the Tribune) hailing the Savoy’s recent refurbishment.[1] This was expanded into a full-page ad in the Tribune in January 1907.[2]

Figure 3: Advertisement in the New York Times, 22 November 1904

In the coming years, however, the Savoy began deploying more crafty techniques in the New York City market. A piece entitled ‘Home Letters of a Contented Exile’ is a particularly effective example of how literary prose, the literary heritage of England and the landscape of London, specifically the Strand, were used to affectively engage American readers, develop the Savoy brand abroad, and cultivate an American customer base for the hotel.

‘Home Letters of a Contented Exile,’ which was published in the New York Times, was an unattributed full-page piece of epistolary fiction which appears to have debuted in June 1909. I don’t want to overstate its impact, as it seems it only ran in the Times on five occasions (7 June 1909, 25 October 1909, 6 June 1910, 26 September 1910, 7 October 1912), once in the Philadelphia Inquirer (18 May 1910) and once in the Chicago Tribune (22 March 1910). But this constituted a significant ad-buy for the Savoy and the style of the ad marked a notable change in the brand’s marketing tactics.

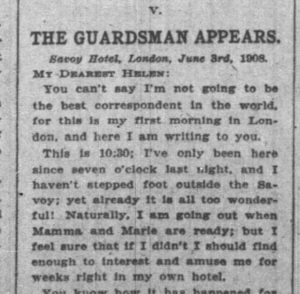

Figure 4: Advertorial in the New York Times, 7 June 1909

In the Times, ‘Home Letters’ appeared where the Savoy’s ads typically ran and a banner of ‘FOREIGN HOTELS’ scrolled atop it, establishing it as advertising content. There was some dissonance between the piece’s location and its romantic content—it might have been more comfortably situated near the women’s section than sandwiched between the sports and financial pages. However, the page’s banner was the only explicit indicator that the aims of the piece might be commercial rather than literary.

In ‘Home Letters,’ a young American woman named Katherine, who has gone abroad with her family, writes her boyfriend, Jack, and her friend, Helen. The story unfolds across fifteen letters and her love life is the central drama. In the first few letters, we discover that Katherine’s father has taken her to England to separate her from Jack. Katherine protests to Helen that her father does not understand her situation: ‘Of course such a thing as either Jack or I ever changing our minds is too ridiculous to even think about. Why, the very night before we sailed, Jack said that the sun rose and set wherever I was.’ Upon arriving in London though, her head ‘full of Dickens and Thackeray,’ Katherine’s interests shift.

There is no reference to the Savoy until deep into the second column of copy.

Figure 5: Advertorial in the New York Times, 7 June 1909

It surfaces discreetly, first in the heading of the fifth letter, and then in the letter’s third paragraph, when Katherine informs Helen that, ‘until I arrived at the Savoy, I almost regretted that we weren’t going to some quiet musty old place with moth-eaten furniture and decayed waiters of the mid-Victorian era.’ Upon her arrival though… no regrets! Only excitement and surprise:

‘Well, I looked at the Strand—I knew we were getting close to the hotel—and I thought I foresaw trouble for Dad if he was lodging us near such a roaring torrent of a street. And then we turned suddenly off the Strand, passed under a great flying arch of stone into the darlingest sort of little court, paved with huge square blocks of rubber, to the hotel entrance, and I saw that quiet would be possible right in the heart of London.’

The hotel provides a ‘picture of fairy romance.’ Its exclusivity is established almost immediately, when Katherine encounters ‘a beautifully gowned Frenchwoman in tears because she couldn’t get a room,’ at which point Katherine ‘realized why Papa had cabled to reserve ours.’ There is high demand for this haven… subtext: readers, book soon!

That is, if readers realized this story was an advertisement for the Savoy. The introduction of the hotel is subtle enough that it is successfully integrated as an important character within the plot rather than the product this romance story is trying to sell.

Mind you, Katherine talks a lot about the Savoy, at length and in detail, debunking myths about English life and accommodations along the way. The suite, comprising three bedrooms and a ‘big salon’ is ‘so comfortable that we hated to go downstairs for breakfast—and we didn’t.’ ‘Who was it that told me there were no bathrooms in England?’ Katherine asks. ‘We have a beauty.’

They also have daylight. “[T]here is sun in London,” Katherine informs Helen, “in spite of all you heard.”

‘[T]he most wonderful thing,’ though, is the view. According to Katherine, each room opens onto a balcony overlooking Embankment Gardens, ‘the most lovely, peaceful stretch of waving green trees and grass and flower beds’ beyond which lie ‘a broad roadway by the river’s edge’ and then ‘the broad brown stream of the Thames,’ ‘the tower of the Houses of Parliament and to the left the dome of St. Paul’s, and over all is the wonderful dim golden hazy London sunlight.’

The view, she writes, ‘holds one entranced.’ The charms of a guardsman, Captain Egerton Fitzmaurice have entranced her too and the narrative pivots to her ‘adorable time’ in London, specifically at the Savoy. At lunch with Captain Fitzmaurice and his friend, they all wax on about the hotel’s wonders. ‘London is the world metropolis,’ she concludes from this, ‘the real center of things.’ ‘[W]ithout stirring, I’m on historic ground,’ she tells Helen, noting that the Savoy is located on the site of what was formerly Henry VIII’s Thames-side Palace. ‘I’d rather be an American girl at the Savoy Hotel than one of Henry’s wives at the Palace of the Savoy,’ she confesses.

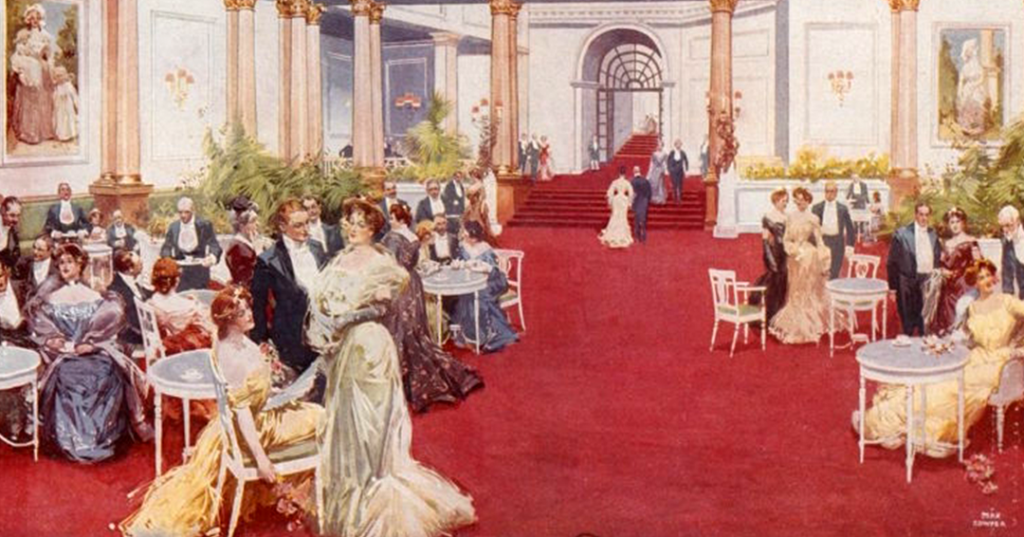

The Savoy’s restaurant circa 1905, as dpicted by Max Cowper for Le Figaro-Modes (image via the Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Through these letters, London is established as the center of the universe and, in it, the Savoy is the place to be, providing ‘a never-ending human panorama.’ Even ‘one or two funny Americans of the kind one only meets travelling,’ ‘Even they had heard in their strange Bloomsbury boarding-houses that they ought to come down here just once to supper and see life.’ Bloomsbury, then, was for losers— the Savoy was where it’s at.

At the piece’s conclusion, we learn that, in their final moments together, Captain Fitzmaurice at long last made his move (holding her hand, he whispers in her ear!) and the couple have made plans for him to visit New York. Katherine also reveals that her father has already booked the same rooms at the Savoy for the following summer. She concludes the final letter with a post-script: ‘Really, I just love—the Savoy.’

Through a simple story of travel romance, ‘Home Letters’ would have enabled American readers—who may never have been to London— to love the Savoy too. It provided copious detail so one could imagine the hotel and, crucially, imagine one’s self in it. That the story is told from an American perspective would likely have added to its effectiveness, lending it far more authority with American readers than a traditional advertisement by the Savoy could have hoped to achieve. As a testimonial, the piece establishes the Savoy brand as deluxe, familiar, romantic, and just English enough to provide a proper English experience while still meeting American expectations of plumbing and luxury.

[1] Savoy Hotel, advertisement, New York Times, 22 November 1904, p. 12, available from: https://www.newspapers.com/image/20460354

[2] Savoy Hotel, advertisement, New-York Tribune, 19 January 1905, p. 4, available from: https://www.newspapers.com/image/186229451

[…] final cut across the Strand led to the side of the Coal Hole pub (built in 1903 as part of the Savoy Hotel estate), down the steps of Carting Lane and across Victoria Embankment Gardens, with a final stop […]