Indigenous actors at the heart of empire: A letter from the Strand to Buffalo Creek

Posted in 1800-1899, 19th Century, people, Stories, Strandlines, theatres and tagged with 1800s, actors, Buffalo Creek, Drury Lane, Indigenous, Seneca Nation, theatre

In 1818, seven members of the Seneca nation were in London performing in the Theatre Royal on Drury Lane. The Hartfort Courant, an American newspaper that ran in Connecticut, published a letter they intercepted from the performers to their families and friends. Through the words of the performers themselves, this article hopes to highlight their lives in London and the impact they had on Strand history. It must be noted that all the sources surrounding the presence of these Indigenous peoples are heavily marred in colonial and white supremacist language. This article has intended to celebrate the Seneca performers’ agency in the city without falling into the cycle of exoticism. If it has failed to do so, please feel free to reach out and let me know what sections could be amended.

Important background information:

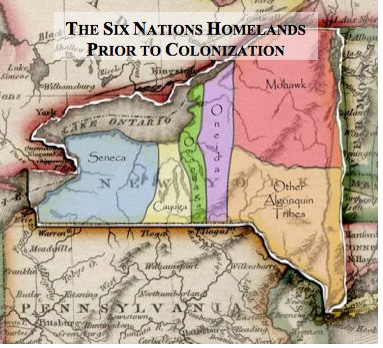

It is important for the reader to understand a brief history of the Seneca nation. “With a proud and rich history, the Seneca were the largest of six Native American nations which comprised the Iroquois Confederacy or Six Nations, a democratic government that pre-dates the United States Constitution.” Its territory spanned “the Finger Lakes area in Central New York, and in the Genesee Valley in Western New York, living in longhouses on the riversides.” – From Culture, Seneca Nation. 1

This is depicted in the map below, from the Iroquois Genealogy Society, which may help the reader to better grasp the scale of this territory. 2

The Six Nations Homelands Prior To Colonization.

The history of the nation in the years leading up to 1818 was tumultuous. In the American revolution, they had sided with the British leading to grave consequences when the American republic was established. As outlined by Britannica, “Major General John Sullivan destroyed their villages in 1779. In 1797, having lost much of their land, the Seneca secured 12 tracts as reservations.” 3

This leads us to the early to mid 1800s, when the Seneca performers were in London.

“Efforts to remove Senecas from their lands culminated in the Treaty of Buffalo Creek in 1838, by the terms of which the four remaining Seneca reservations’ Buffalo Creek, Tonawanda, Cattaraugus, and Allegiant·ere sold and provisions were made for the Senecas to remove to Kansas. The corrupt proceedings were protested, however, and a new Treaty of Buffalo Creek was signed in 1842. The new agreement stipulated the sale of Buffalo Creek and Tonawanda, but retained Allegany and Cattaraugus.” – From Treaties, Seneca Nation.4

Just twenty years after the performers worked in the Theatre Royal, the United States government began to force the Seneca Nation off its remaining land. The loss of Buffalo Creek resonates in particular as it is where the letter of the performers was addressed.

This increasing colonising pressure by the United States culminated in the Seneca nation splitting into two. In 1848, a Seneca republic was declared “the Seneca Nation of Indians” while the “Tonawanda Band of Seneca” continued separately. The former declares, “the modern day Seneca Nation of Indians is a true democracy whose constitution was established in 1848.” From Government, Seneca Nation.5 The Tonawanda are described as, “a federally recognized tribe in the State of New York. They have maintained the traditional form of government led by hereditary Seneca chiefs (sachems) selected by clan mothers.” 6 It is important to note that the latter source is not written by the Tonawanda government itself, but, reported by a third party religious organisation.

A letter home:

On August 24th 1818, the performers wrote home from the Strand, London . (A photo with the full text can be found at the end of the article.)

They began “To the cheifs (sic) of the Seneca nation, residing on the Buffalo Creek, and friends of the warriors of that nation now in England: Fathers, countrymen and friends.” 7

This tells us two important things. Firstly, the Seneca nationals had befriended some Londoners during their stay. Secondly, it reminds us that the seat of the Seneca nation was still in Buffalo Creek at this time.

It continues, “In the season of the year when the leaves last fell from the trees, we met with you in council, and agreed to take upon ourselves the great expedition, in which we are now engaged . You then reminded us of the exploits of our ancestors, and the hardships they had endured; and advised us to go forward, be strong, and conduct ourselves like men.” 8

From this phrase we can suppose the performers left around autumn (or fall) the previous year, 1817. Since the letter is dated for late august 1818, they have been away from home for around a year at the time of the letter.

“It has pleased the Great Spirit to conduct us from our settlements on the Buffalo Creek, to this great city, in safety, good health and high spirits, (with but few exceptions, and those such as are incidental to persons when performing long journies) for which we are very thankful.” 9

Here the reader is indirectly told that some Seneca performers were affected by the journey to London. Whether simply sick or worse, there is no more information. This is not surprising given that sailing ships were taking around six weeks to cross the Atlantic. 10 The emerging packet ships only began service in 1818 with the Black Ball Line, and the fastest of the ships could see a passenger from New York to Liverpool in seventeen days. 11

Fears surrounding their journey?

The letter addresses the fears of some Seneca citizens concerning the trip to London.

“Fathers you may still remember, that when we, your children, were first called upon to come ‘o this country, that there were some of our people, who, through their friendship for us, opposed our undertaking; as they were fearful that we should be sold for slaves to the inhabitants of this island; and others, that we should be disgraced by living shut up like cats, for strangers to stare at. But, Fathers, we boast a prouder station than such friends were willing to assign us. The great spirit has been mindful of his red children in the foreign country; and instead of being sold for slaves, we have found kind friends, who have made us happy by inviting us to their homes,” 12

This highlights the fears felt within Buffalo Creek when seven of them left towards the heart of the British empire, London. These fears were completely justified. Britain was one of the biggest contributors to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. On a side note, the UK’s National Archives should heavily reconsider the way it discusses Britain’s involvement in this wretched period of history. It claims “Britain was one of the most successful slave-trading countries.“13 Britain contributed to the death and destruction of other nations and this should never be viewed as a success.

Moreover, the idea of being ‘put on display’ was a very real threat. White supremacist ideology, which promoted imperialism, ‘othered’ non-white peoples. This led to the creation of ‘human zoos’. These were effectively prisons in European capitals to ‘show-off’ various peoples from colonised nations. Sarah Bartmann, from South Africa, is a prime example in the early 1800s. “In 1810 Peter Cezar arranged to bring her to London, where he put her on exhibition in the Egyptian Hall of Picadilly Circus. She appeared on a platform raised two feet off the ground. A “keeper” ordered her to walk, sit and stand, and when she sometimes refused to obey him, he threatened her.” 14

It seems, however, that the Seneca performers were not treated poorly by their employers in the Theatre Royal. They even go on to say, “we are as much at home, and every way as much at liberty in London, in every respect, as we could be, were we at our settlements on the Buffalo Creek.” 15

We do not have to rely only on their words, which may have been distorted by the Brits and Americans involved in the publication of this letter (the letter was sent “by Augustus C Fox,” a Brit, “in behalf of the party.”) 16 The actions of the performers seems to corroborate the letter, as they remained in London for a few more months than initially intended. This suggests they did, in fact feel at home in London.

Who were these performers?

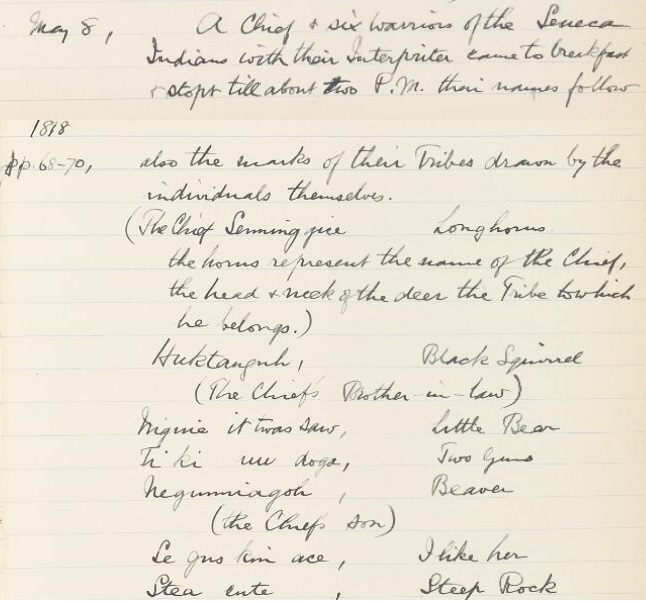

It is important to name these performers. The letter does not give us any names of performers except for “NE-GWI-E-ET-TWAS-SAW” as one of the signatures finishing the text. Through important research undertaken by Harold Hunt, much more information about the Seneca performers can be uncovered. The names of the performers are as follow: Senung-gis, Ne qui-e-et-twassaue, Sta-eute, Uc-tau-goh, Ne-gun-ne-au-goh, Se-quos-ken-ace, Te-ki-eue-doga. 17 He later explains the translations of those names in English. 18 By using a print depicting the performers and Hunt’s drawings, the names of the performers can be linked to their correspondent translation.19

The seven Seneca performers in print. Titled “The North American Indian Warriors, from Lake Erie, of the Tribe of Seneca, who were in London in 1818.”

- Ne-gun-ne-au-goh – Beaver

- Se-quos-ken-ace – I like her

- Te-ki-eue-doga – Two guns

- Sta-eute – Steep rock

- Uc-tau-goh – Black squirrel

- Senung-gis – Long horns / The chief

- Ne qui-e-et-twassaue – Little bear.

By visiting the Retreat in York, the seven performers left their signatures in the visitor’s book. 20 Harold Hunt then began to search for a print of the seven Seneca nationals. His extensive back-and-forth with various museums and print shops is documented over forty-five pages. In a very tangible sense, this showcases their impact on English history. They travelled around this country, interacted with many people, in various cities, and left a trail for us to follow.

The Seneca performers are signed into the The Retreat visitors book.

How did they impact Strand history?

It is clear from this trail that these performers travelled the country and befriended various English people. But what was their impact on the Strand? The first impact is the basis for this whole article, their letter. It was, “dated Head-quarters, theatre royal, English Opera Strand, London, August 24th, 1818.” 21 Now, admittedly, the Theatre Royal is on Drury Lane. Still, the letter is sent from the Strand and we will continue with that assumption.

They performed in a play that was steeped in exoticism. Whoever wrote the play clearly desired to lean into the mentality of ‘us versus them.’ I will not focus on the subject of the play, however, Harold Hunt’s notes contain a program which outlines its content. 22 The impact of their presence as part of the play is far more important. J.C. Greene has compiled theatre reviews from the past two centuries, including two concerning “The Indian Settlers” from 1818 and 1819. 23 In these, there are two key quotes.

- “First time in this kingdom a ballet consisting of a chief and five warriors of the Seneca Nation (who had just been performing in the Lyceum in London.” 24

- “The House was crowded.” 25

These two quotes tell us two rather simple things. There was never before a Seneca performer in a British ballet. Moreover, the play was very popular. This latter point also helps to explain why the performers opted to stay longer and continue their performances.

Lastly, their impact is seen by this article being written. They were a part of the Strand’s, therefore London’s, history for over a year in the early 19th century. Their presence in the UK was not forgotten. This article, among the many other sources, prove their continuing importance.

Concluding thoughts:

These seven performers laid the foundations for future Seneca nationals to come to Britain. In the mid 19th century, a long-distance runner named Hutgohsodoneh came to compete in Britain and Ireland. Coll Thrush describes him as “a hugely famous man known as Deerfoot, right in the heart of Hackney.” 26

Thrush continues, “His English name was Louis Bennett, and he was a member of the Seneca Nation of western New York, among whom his name was Hutgohsodoneh, “He Peeks Through the Door.” Between the fall of 1861 and the spring of 1863, he electrified audience throughout Britain and Ireland. […] It was his London performances, though, that would draw the most attention, in terms of both numbers present and coverage in papers around the nation.” 27

Indigenous visitors in London were not, however, limited to the Seneca nation. Thrush points out that many peoples from various nations influenced London’s history. As he puts it, “These strands came together at a series of large-scale Indigenous spectacles in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A Seneca runner, a group of Aboriginal Australian cricketers, a Māori rugby side, and Lakota Wild West Show performers all riveted London, and their presence there tells us much not just about Indigenous visitors but about Victorian and Edwardian – and imperial- culture.” 28

Therefore, we can see that these Seneca performers were the first in a line of Indigenous peoples who impacted London’s history. The interested reader may wish to refer to Coll Thrush’s “Indigenous London” to further explore this rich history.

Following the trails of history from Buffalo Creek, to the Strand, to York, and back again, has been extremely rewarding. The discovery of Harold Hunt’s notes emphasised the extent of the impact these seven men had. In the 1920s letters to various museum directors and print shops, Hunt revived the discussion surrounding the time these Seneca performers spent in London. Around a century later, this article hopes to continue this discussion surrounding the impact of Indigenous actors on London’s history, specifically concerning these seven Seneca actors.

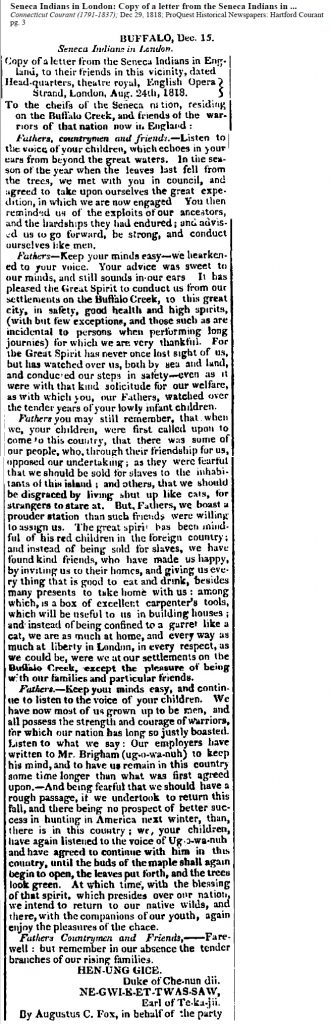

As promised, below is a copy of the letter from the Seneca performers to Buffalo Creek.

A copy of the letter from the Seneca performers back to Buffalo Creek.

- Culture, Seneca Nation, https://sni.org/culture/, Accessed July 22nd 2021.

- Iroquois Genealogy Society, ‘The Six Nations Homelands Prior To Colonization Map’, Iroquois Genealogy Society, accessed 24 July 2021, https://www.iroquoisgenealogysociety.org/master-map-gallery.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Seneca | History, Culture, & Traditions’, Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 30 July 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Seneca-people.

- Treaties, Seneca Nation, https://sni.org/culture/treaties/, Accessed July 22nd 2021.

- Government, Seneca Nation, https://sni.org/government/, Accessed July 22nd 2021.

- Native Ministries International, ‘Tonawanda Band of Seneca’, accessed 30 July 2021, https://data.nativemi.org/tribal-directory/Details/tonawanda-band-of-seneca-198450.

- ‘Seneca Indians in London: Copy of a Letter from the Seneca Indians in England to Their Friends in This Vicinity, Dated Head-Quarters, Theatre Royal, English Opera Strand, London, Aug. 24th, 1818’, Connecticut Courant (1791-1837), 29 December 1818, 548533744, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Hartford Courant.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- ‘Benjamin Franklin . Worldly Ways . Atlantic Ocean | PBS’, accessed 22 July 2021, https://www.pbs.org/benfranklin/exp_worldly_atlantic.html.

- Stephen Fox, ‘“Transatlantic”’, The New York Times, 14 September 2003, sec. Books, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/14/books/chapters/transatlantic.html.

- ‘Seneca Indians in London: Copy of a Letter from the Seneca Indians in England to Their Friends in This Vicinity, Dated Head-Quarters, Theatre Royal, English Opera Strand, London, Aug. 24th, 1818’

- The National Archives, ‘Slavery and the British Transatlantic Slave Trade.’, The National Archives (blog) (The National Archives), accessed 22 July 2021, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/british-transatlantic-slave-trade-records/.

- M. Lederman and I. Bartsch, The Gender and Science Reader (Routledge, 2001), 351, https://books.google.ca/books?id=9obFtmhcCNsC.

- ‘Seneca Indians in London: Copy of a Letter from the Seneca Indians in England to Their Friends in This Vicinity, Dated Head-Quarters, Theatre Royal, English Opera Strand, London, Aug. 24th, 1818’

- Ibid.

- Harold Hunt, ‘Notes and Papers on the Seneca Indians Who Visited The Retreat 8 May 1818’, The Retreat, 1930s, 16, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nwv4f67q/items?canvas=1.

- Ibid, 28

- Dennis Dighton, ‘The North American Indian Warriors, from Lake Erie, of the Tribe of Seneca, Who Were in London in 1818’, The British Museum, accessed 23 July 2021, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1926-0511-45.

- The Retreat, ‘Notebook of Extracts from the Early General Visitors’ Books 1811 – 1861 and Notes on Some of the Visitors Named’, Wellcome Collection, 73–75, accessed 23 July 2021, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/uc3vfpq7/items.

- ‘Seneca Indians in London: Copy of a Letter from the Seneca Indians in England to Their Friends in This Vicinity, Dated Head-Quarters, Theatre Royal, English Opera Strand, London, Aug. 24th, 1818’

- Hunt, ‘Notes and Papers on the Seneca Indians Who Visited The Retreat 8 May 1818’, 4.

- J.C. Greene, Theatre in Dublin, 1745-1820: A Calendar of Performances, Online Access with Subscription: Proquest Ebook Central (Lehigh University Press, 2011), 4361, https://books.google.ca/books?id=boLmd-KxZ9oC.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Coll-Peter Thrush, Indigenous London, The Henry Roe Cloud Series on American Indians and Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 178, http://books.scholarsportal.info/viewdoc.html?id=/ebooks/ebooks3/oso/2017-05-04/1/upso-9780300206302.

- Ibid. 179-180.

- Ibid. 175.